by Alyson Haley

It was the first practice of the varsity volleyball season for senior Sam Johnson, and a simple landing took her out of both volleyball and track. Everyone thought that it was just a sprain; the pain was there for a few minutes and then it was gone. It was just a funny landing, something anyone could make.

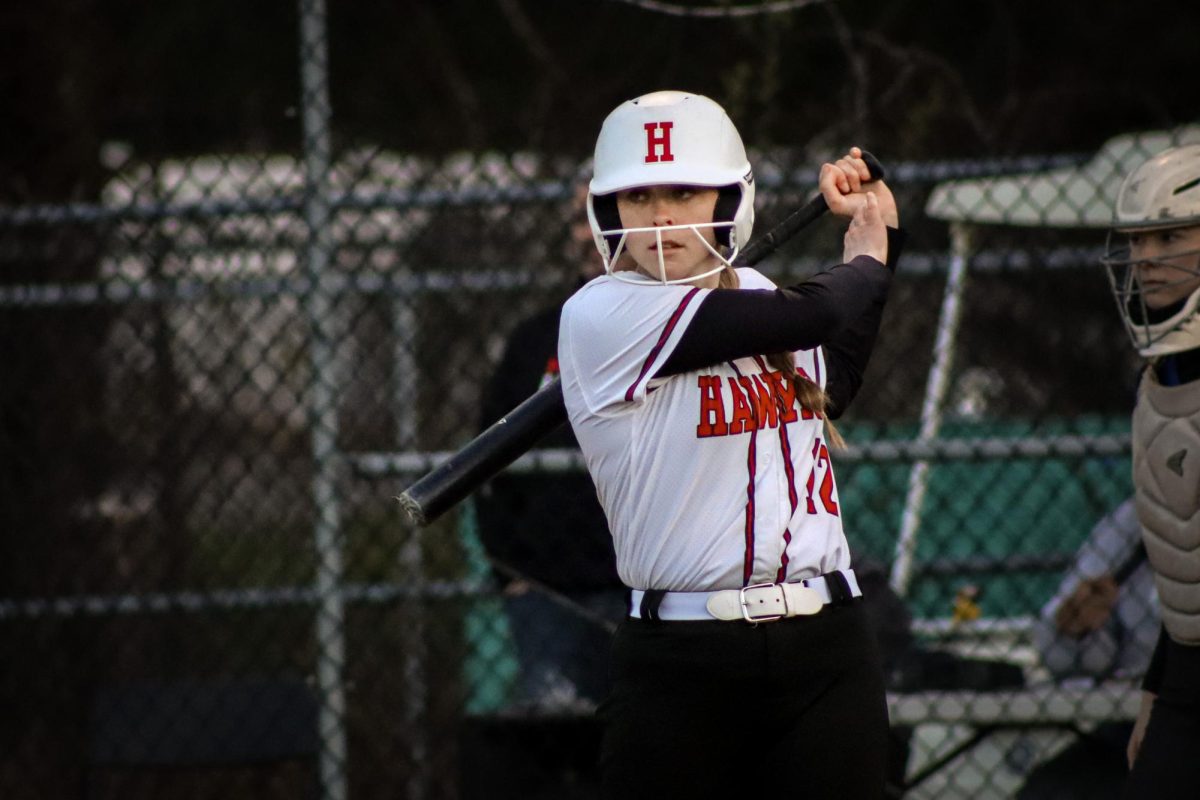

Johnson normally plays the position of libero, a player specialized in defensive attack and skills, but this year her coach wanted to try her out as an outside hitter. When they had set up in hitting lines at the beginning of practice, Johnson jumped up to do an outside hit, a hit aiming into the middle of the court, and when she landed, she tore her ACL.

The anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, functions mainly in preventing “knee instability by keeping the tibia from sliding forward in relation to the femur. It functions secondarily to restrict excessive knee extension, varus and valgus knee displacement, and tibial rotation. Additionally, the ACL protects the cartilaginous shock absorbers of the knee (the menisci) from damage that could occur while jumping, cutting (rapid deceleration associated with a quick change in direction), and pivoting in sports,” says Dr. Aisha Dharamsi and Dr. Cynthia LaBella in their article from Contemporary Pediatrics on ACL injuries in young female athletes. An injury, such as a tear, is caused by either a complete or partial over stretch of the ligament.

“I didn’t really think anything of the pain. It was kind of an excruciating pain for about ten minutes, but then after icing it the pain was gone,” says Johnson. “We all thought it was only a sprain. With that I would only be out for two weeks, but I ended up being out eight months.”

For Johnson, the most pain she suffered was not being able to play with new teammates and a new coach.

“I just really wanted to play with my team this year,” said Johnson. “I was so excited to play my senior year. At first it was really hard. Watching the team from the sidelines was kind of devastating. But I got to the point where I knew that I couldn’t play. I’ve become okay with sitting on the sidelines, cheering on my teammates.”

Johnson is just one of the several ACL tears that Hudson High has seen this year. Since Athletic Trainer Britteny Gentile began her job here, she has seen around thirteen ACL tears, almost half of them have been in this fall season alone.

“The kids joke around all the time that it is my fault this keeps happening,” says Gentile. “They say it never really happened before I got here, but there is no clear reason. It just keeps going up.”

An ACL tear is not something that can be prevented, though Johnson did take every precaution she could from knee braces to double ankle braces. Johnson was known in her family as the “sturdy child.” She never really sustained a serious injury.

ACL tears are almost always caused without contact with another person. They are more than likely the effect of an athlete’s landing from a jump, like Johnson’s, or a quick change in direction, like sophomore Elizabeth Campbell’s.

With the rise of intensity in youth and high school sports, it is almost inevitable that ACL injuries rise, too. More and more athletes are starting to play high intensity competitive sports at very young ages. The exposure to such high intensity activities may build muscle, but it also wears down the ACL, making it weaker further into the athlete’s life.

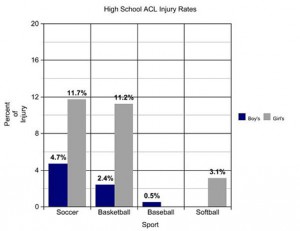

Dr. Dharamsi and Dr. LaBella say that it is unlikely for someone under the age of twelve to experience an ACL tear. They more frequently begin to occur in girls ages twelve to thirteen and ages fourteen to fifteen for boys. Female athletes are around five times more likely to sustain this kind of injury than males.

This holds true for the injured athletes at Hudson High School. Around eight of the thirteen injuries have occurred in our female athletes, while only five have been in male athletes.

Campbell is a three-season athlete, like Johnson, who tore her ACL during a varsity soccer game in early October. Both Campbell and Johnson are teammates in varsity indoor and outdoor track.

“I never thought that this would happen to me,” says Campbell. “I had just always thought that my legs were stronger. “

Some athletes, like Campbell, are going to have the chance to continue on in their high school career, but if she had torn it a year or two later, she might not be so lucky.

The road to recovery for everyone is long and grueling. Including physical therapy the physical healing process can take at least six months.

Both Johnson and Campbell have been going through almost identical treatment courses. Physical therapy and crutches about a month before surgery, as well as after surgery. Physical therapy post operative can go on for as long as six months.

Recently athletes have started to go through pre-operative physical therapy to help speed along some of the healing process. Physical therapy before the surgery limits any post-op complications, improves the chances of a full return to sports, and minimizes the risk of a second ACL tear.

Though the physical recovery process is incredibly important to restoring the athlete’s health, the mental strain it puts on the athlete is a lot to handle.

Gentile says that her role as the athletic trainer isn’t to help them physically, but to support them and help coach them through their recovery.

“I see a lot of the kids just being down on themselves,” says Gentile. “Once they can start to see the light at the end of the tunnel, everything becomes a big deal to them. Getting off crutches, getting their brace off, and riding the bike. Those little things help them push through, and if I can encourage them to push through, then that’s awesome.”

For many seniors the recovery process can be very depressing. They don’t see anything to look forward to in their sport. Even with the encouragement from Gentile, it is hard. They watch from the sidelines and participate off the field, but that is all they can do. It gets torturous.

Johnson though has chosen to look on the bright side and not let the injury get her down. “I mean I won’t be able to participate the rest of this year, which isn’t fun, but hopefully if I go to a D3 school, I’ll be able to play volleyball. That is kind of like a dream scenario, and if I don’t make the team, I can always play club.”

Johnson is expected to make a full recovery by May of this year. Though she will not be able to compete in spring track, she is looking forward to assisting in unified track and being able to jog alongside them in their races.

Luckily for Campbell she should be able to participate in all sports in the next school year. After she has the all clear to begin jogging and exercising again, she is planning to take the summer to really get back into soccer shape. With the help of her sister Mary, who also tore her ACL in soccer last year, she is hoping to be at almost the same level as she was earlier this year.

Like any athlete who returns to a sport after a serious injury, Campbell has a few fears about what may happen in the future.

“I’m so nervous to go back, but I’m ready,” says Campbell. “I know that I am weaker in my legs, and I won’t be as strong or as fast as I used to be, but I’ll get there. My focus is just getting back out there for the fall and making it through preseason.”