by Dakota Antelman

Katherine Neff remembers attending meetings at the UN.

She remembers her awareness of the bureaucracy of it all.

She remembers the scheduling conflicts which that bureaucracy beget.

And she remembers that, while those conflicts played out, bloody ones raged a world away.

“To know that there are children being abducted by Al Qaeda while we are trying to have a meeting…that part was frustrating,” she said.

Now a Hudson High School social studies teacher, Neff traveled around the world during and after college, holding jobs at four different organizations all loosely unified around the principle of helping war or poverty stricken communities advance. Her work acquainted her with Haitians recovering from the earthquake that devastated their country in 2011. It introduced her remotely to the plight of laborers in Zambian and El Salvadorian sugar fields and to humanitarians in Malawi opening opportunities for girls to go to school. Then, her work sent her to war torn Ugandan communities where she helped plan access to clean water.

She also landed behind desks in Washington, D.C., and New York and specifically, in meetings at the UN and supporting attendees of meetings at the US Capitol Building among other places.

Neff left international aid after years spent both stateside and abroad. But, before she did, she learned lessons that she applies to her new career as a Hudson High School history teacher.

Much of Neff’s international work focused on helping communities and their members see beyond their often restrictive circumstances to get educations or to improve their health.

In Hudson, she continues to employ that philosophy, now helping her community of students see beyond the circumstance and stereotypes that life in a free and comparatively affluent society gives them.

Early in her career, Neff collaborated with schools in Malawi working to break cycles of child marriages to get young girls into schools and careers.

These communities had, for generations, effectively sold their young daughters into those marriages. Few girls went to school. Many simply stepped from childhood into the homebound lifestyle deemed traditional for women.

Neff’s organization, Advancing Girls Education in Malawi, wanted to change that. In doing so, they set a goal to get 14 year old girls into school and, within five years, see 80% of those girls graduate and/or enter careers.

“They had good numbers of girls who were able to go to school, stay in school and go into some sort of career beyond the traditional roles that women play in Malawi,” she said. “There was enough buy in on the ground from people.”

But, she added, in seeing generations of tradition challenged, some in those communities pushed back.

“There can be backlash where people have these entrenched roles,” she said. “That is a big topic of discussion in the field of international development.”

Changing those entrenched roles proved to be a line running through much of Neff’s time in Africa.

Later in her career, while working with the Clearwater Initiative, a Ugandan NGO, Neff and her colleagues served as educators, pushing a local community to practice better hygiene with their water usage.

Waterborne illnesses ran rampant in at least one community. The stream from which they were drinking was to blame. But the community members would not stop drinking from it. It was the same stream from which their ancestors drank.

Knowing that, Neff, her organization, and the community sought solutions that kept the community drinking out of the same stream without getting sick.

In other places, Neff and her organization taught communities to keep their animals away from clean water supplies and wash their hands before using wells among other things.

“Clean water is great, but if you do not have the hygiene and sanitation and education parts down, too, clean water is ridiculous to have,” she said.

All through her international aid career, Neff taught people to look beyond the traditions and lifestyles with which they were familiar.

In Uganda and Malawi, those were generations-old traditions of drinking from the same stream. They were habits of letting livestock walk right up to riverbanks. They included an expectation that girls would skip education, marry young and never work.

In Hudson, meanwhile, most girls not only go to school, but attend college. Clean water runs from a tap. And food comes from the supermarket, rather than from a live animal by the local river. Traditions and lifestyles here clearly differ from those Ugandan ones. Their strength in shaping perceptions of the outside world, however, is just as strong.

Many she met in Uganda, Neff remembers, believed stereotypes about the outside world.

“They think the U.S is a bunch of fat people eating McDonald’s, which is not the case as all,” she said. “It’s much more complex and different than people think.”

Likewise, some of Neff’s current students hold stereotypes about the corners of the world they’ve never seen.

“Isn’t Africa just desert?” one student once asked Neff.

No.

Using moments like those, Neff now hopes to, with her lessons, break those stereotypes American students have about the very countries she saw first-hand.

“It is just misconceptions because those are the stories we are fed growing up,” she said.

She shares pictures of Africa’s sprawling cities to show students the differences of culture, lifestyle and geography even within the continent. From time to time, she shares stories of her time there.

“I think at 14 years old, you are thinking that a lot of places are strange and far away,” she said. “They don’t have exposure to it.”

Near the end of Neff’s career abroad, tensions in South Sudan ignited into armed conflict. Roughly an hour’s travel away from such active violence, Neff began reevaluating her career path from a personal perspective.

“We were a little nervous while we were there,” she said. “Thinking about it long term, what was my career going to look like? What was my life going to look like?”

The answers to that final question continue to unfold. Neff met and married a man who, like her, saw the impact of human tragedy first hand — he is a veteran of conflicts in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

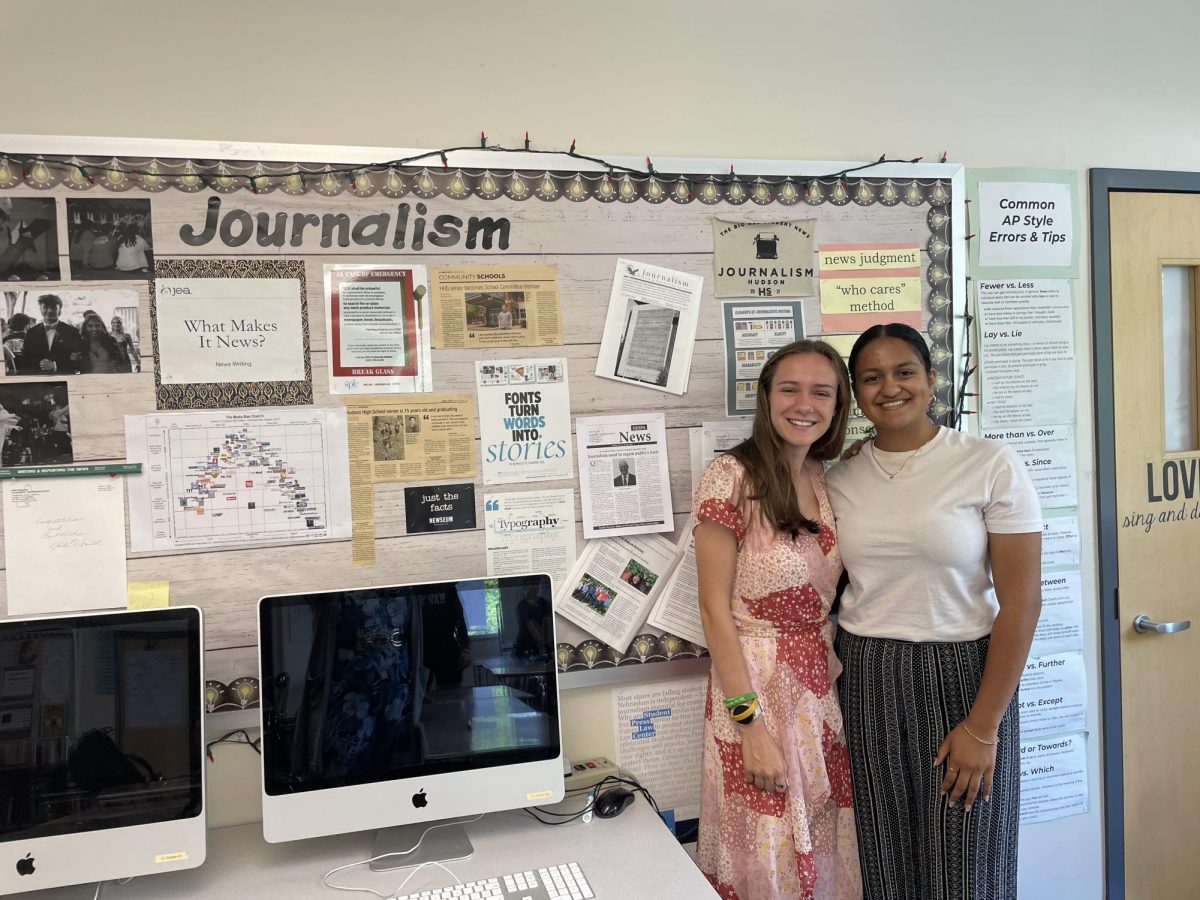

She then left Africa and came to Hudson. Neff is teaching now, her life contextualized not by systemic violence, subjugation, and inaccessible education, but by the hallmarks of suburban America.

6,500 miles removed from her informal classrooms in Uganda, however, Neff still teaches with the same mindset about broadening students’ worldviews. She finds the same joy in doing that she did in Africa.

“Being in the classroom, I am getting that same sort of feeling that I had on the ground in Uganda — the one on one, working with kids is amazing,” she said, later adding, “I love it.”

CORRECTION

3.1.18 – 7:33 A.M – An earlier version of this article incorrectly represented Neff’s work at the UN and the US Capitol. She attended meetings at the UN and supported people who attended meetings at the US Capitol but did not technically work at either location.

![Brazil's Neymar walks onto the pitch during his debut for Santos FC in a Sao Paulo league football match against Botafogo, in Santos, Brazil, Wednesday, February 5, 2025 [Andre Penner/AP]](https://bigredhawks.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Neymar-is-Back-e1743558992671.jpg)

Pamela Porter • Jun 7, 2018 at 2:19 pm

Love articles that highlight our teacher’s diverse backgrounds. Would be interesting to hear more about why she left that sector or what advise she has for the many students heading into political or non-profit sectors.