Nancy Tobin speaks in a Hudson High School classroom. | by Dakota Antelman

by Dakota Antelman

Nancy Tobin spoke to the friends her son Scott left behind as they all mourned his death at his funeral.

She held those teens and twenty-somethings close and promised to support them if they ever needed help with the disease that took her son — substance use disorder.

“Don’t let this happen to you,” she said. “If you need me, come find me. I really would be there. I would be the person who would go and pick you up and take you to a rehab.”

Roughly eight months later, she was speaking to teens again, not at a funeral, but as a guest speaker in a Hudson High School Wellness class. Indeed, Tobin has taken her story public, joining a growing community of people touched by substance use disorder working to prevent future addictions by describing their struggles.

Families Tell Their Stories after Their Loss

Tobin said she speaks both to process her grief and to help others avoid the trauma she experienced in losing her son.

“I can either sit in the corner of a room with a blanket over my head and cry and never want to move; I fight that feeling every single day of my life now,” she said. “Or, I can stand up and I can say, ‘I’m going to go on, and I’m going to go on because my love is that strong — because Scott’s love was that strong.”

Tobin struggled alongside her son for years. He was first exposed to opioid painkillers after a terrible car accident in his senior year left him with bone breaks in his ribs, feet and wrist, a bruised lung and a concussion among other things.

He still graduated from Hudson High School that spring and moved on to Franklin Pierce University in the fall. His addiction worsened, however, once he was at college.

Over the next five years until his overdose, Scott asked for help. Unfortunately, many of the treatment centers his mother sought for him turned Scott away, saying they had no open beds.

As her son struggled to get help, Nancy Tobin said Scott told few people about his addiction.

In speaking publicly, Tobin hopes she fights the stigma surrounding drug use that she said caused Scott to keep that pain quiet.

“It’s one more thing, that, if they let it out into the open, they’ll lose any bit of credibility that they once had,” she said about drug addiction. “That’s a very hard thing to be in a situation like that. Again, why do we do that to people?”

She continued, saying that stigma persists even though recently soaring drug overdose rates have included several young people killed in Hudson alone.

“It still makes people very uncomfortable, and that discomfort makes people want to sort of still turn their head and wink and whisper about it,” Tobin said. “[They say], ‘That happened because so-and-so was hanging around with the wrong people,’ or that it was bound to happen because of something that they have heard. There is a lot of rumoring and a lot of talking. That’s the piece that has to change.”

Despite the stigma, Tobin realized her story’s effectiveness even mere minutes after her presentation to Hudson High School students. She hugged students who, she said, trembled as they thanked her and told her they knew people who struggle with addiction just as Scott did.

“I will never forget looking around into those students’ eyes and seeing them looking right into mine and feeling as though they were as open to hearing me as I was open to telling them whatever I could that might be of help to them,” she said. “They don’t feel that it’s a joke. They don’t feel that it needs to stay in the shadows. They know it’s real, and that’s what they looked like. They were afraid.”

In addition to her presentation at Hudson High School, Tobin was involved with a recent vigil for overdose victims in Marlborough. Marlborough mother Kathy Leonard, who also lost her son to an overdose, organized that vigil and currently runs a support group that Tobin attends for families of overdose victims. She has also worked with the executive director of the Addiction Referral Center, Marie Cheetham, on fundraising and awareness events for the center, which provides care for recovering addicts.

After her presentation in Hudson though, Tobin said she wants to focus mainly on small-scale, person-to-person conversations going forward.

“I want to really bring this idea of getting rid of the stigma and getting people to realize that it’s everywhere,” she said.

Addicts Tell Their Stories during Recovery

While Tobin provides the perspective of a grieving parent, Dot Fuller speaks as a recovering addict.

Fuller, like Scott Tobin, was a member of the Hudson High School Class of 2012 who struggled with heroin addiction. She remembers getting high with him when the two were younger but had been clean for just over a year when Tobin overdosed.

Part of her recovery, Fuller said, has involved separating herself from the community and acquaintances that she knew while she was using. As a result of that separation, she did not immediately know her friend Scott had died.

Fuller followed in Nancy Tobin’s footsteps, also speaking to Hudson High School Wellness students just days after Tobin’s talk.

Reflecting on her own experience as a student in Hudson, Fuller noted the absence of similar drug use prevention education even just five years ago.

“People came in, but they were all old and no stories hit home,” she said. “Maybe it just wasn’t as relevant when I was in high school, so that’s good that they’re doing more stuff about it now.”

Fuller struggled with drug addiction earlier than many of her classmates. While Nancy Tobin said Scott did not use harder drugs such as heroin until college, Fuller vividly remembers feeling out of control before even starting her sophomore year.

“It turned into a job — like a career — just getting high, not wanting to be sick anymore but not being able to do anything, even to take a shower without getting off E,” she said, using an expression used by many addicts to describe the feeling of emptiness and lethargy when sober. “I was well into that stage by the summer before sophomore year.”

With a pervading feeling that she would be punished by administrators or guidance counselors if she asked for help, and without dialogue about drug use in her school, Fuller remembers feeling disconnected from her school community.

“It was very isolating because Hudson High School was a school where everybody did sports,” she said. “Everybody was so focused on what college they were going to, so I was in Worcester a lot. I related a lot more with the inner city schools. Worcester was the closest.”

Fuller dropped out of Hudson High School before her senior year. In the ensuing years, she managed to get sober and hold a job at Tufts Medical Center. She frequented Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous meetings for support, but she once relapsed after nearly a year sober when she visited Hudson and felt a sudden urge to use again.

Now with close to two years of sobriety, Fuller feels like she has regained some of the control she lost as a teen. Still, she told students during her presentation that relapse remains a very real threat.

As she continues to push back against that threat, Fuller has made appearances like the one at Hudson High School a regular part of her life. She finds them healing.

“When I tell my story to people, I’m practicing honesty,” she said. “That’s one of the biggest things to me, to be honest with myself and be like, ‘This happened, and this is where I don’t want to go back to.’ Hearing myself say it out loud is like a reminder.”

Fuller said dishonesty was a major part of her addiction, in school and outside of it. She explained, “If you asked me what I had for breakfast, I would say a bagel even when I had cereal. It was just a habit to lie.”

In addition to her presentation at Hudson High School, Fuller has spoken at rehab centers she herself attended and visited the MCI Framingham Women’s Prison to make a similar appearance. She has also spoken at other Massachusetts high schools, including Bridgewater High School.

Though she insists these presentations help her far more than they help students, Fuller has seen her story’s impact on teens and addicts.

At one point, a group of people recognized her at a coffee shop after her presentation and thanked her. One said her brother was an addict. Fuller was able to connect that person with treatment opportunities.

“It feels good,” she said. “I’ll go back and visit programs that I’ve been to and speak as an alumnus of the program. When I then go to an AA meeting or something a year later and I see them, they say, ‘Yeah, I’m still doing good.’ That feels wicked good.”

Educators Hope Speakers Change Minds

Fuller and Tobin both found their presentations to Hudson High School students to be beneficial. They only made those presentations, however, because of the willingness of the Hudson High School Wellness Department to bring guest speakers into classrooms.

Wellness teacher Dee Grassey and Curriculum Director Jeannie Graffeo agreed, however, that those recent presentations were not the result of any major changes to the Wellness department’s approach to guest speakers. Rather, they said, simple scheduling issues often decide whether speakers come to Hudson High School.

Hudson’s rotating block schedule does make it difficult for guests to speak to all of a teacher’s classes, which often do not all meet on a given day.

Still, Grassey said the staff’s attitude toward such guest speakers has changed as substance use disorder has affected former Hudson students.

“We couldn’t just be [saying], ‘No, no, no,’” she said. “Kids have to hear real life experiences in order to connect. You have to be able to put yourself in that person’s situation and go, ‘I’ve done that. I’ve been there.’”

Having taught in Hudson since 1994, Grassey said the current wellness curriculum is much better now than it was years ago.

Nevertheless, she and other wellness educators agree that the schools need to devote more energy towards improving student health. Otherwise, Grassey fears, student drug use will only continue.

“I get it,” she said. “If it’s reading, writing and arithmetic over health education, health education is going to get cut. But I think the schools over the years have to take some of this responsibility that, when they’re not consistent, this is the stuff that happens.”

For Tobin, an educator herself, schools also need to change the atmosphere surrounding conversations about drug use.

“[Students] come here, and they can breathe when they come here because we don’t always know what goes on in their lives outside of here,” she said. “Let’s also make it a place where, if they need that kind of help, they can ask for it here and not be afraid of the repercussions.”

She proposed expanding drug use prevention education into Hudson’s middle school curriculum and bringing in public speakers to address staff in an effort to change faculty biases about drug use.

For Graffeo, health is crucial to the success of a student body. As drug use persists and continues to kill many young people nationwide, she wants to bring a better awareness of student health into education.

“What’s the first thing we ask about children when they’re born — are you healthy?” she said. “As we go through education, one common piece is that sometimes we forget that and we focus on test scores. We focus on all these other things, and we forget the fundamental building block, which is health.”

As Crisis Continues, Those Left behind Speak to Save Lives

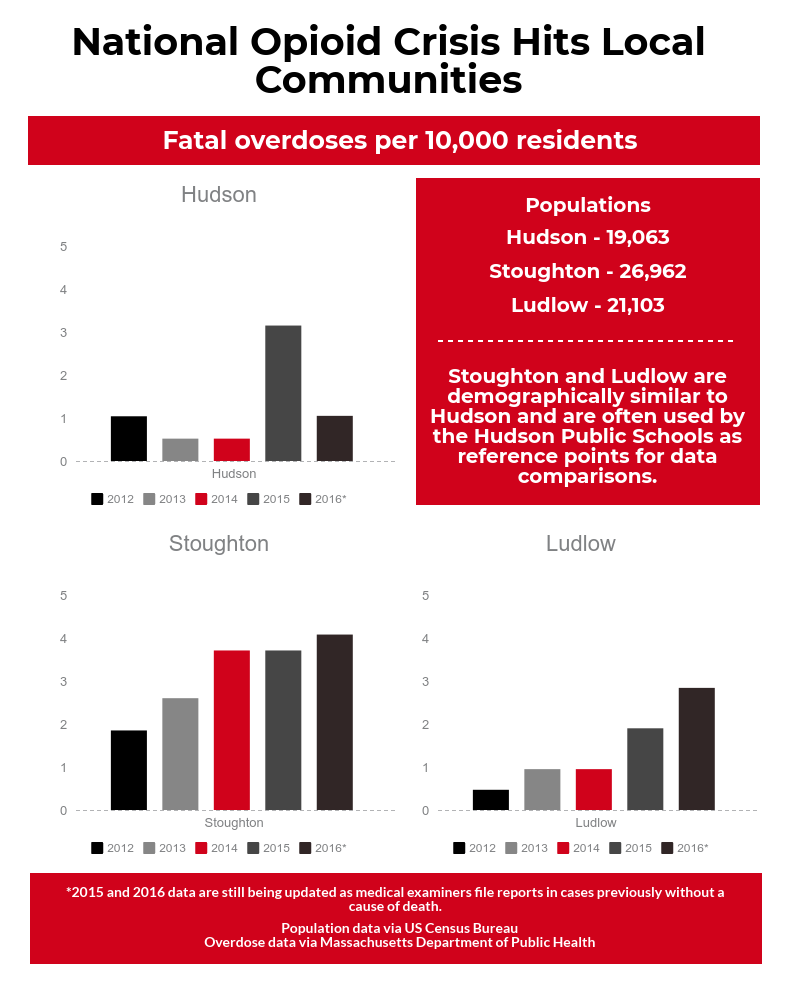

The Hudson Public Schools has said it will not release hard data on student drug use collected by last year’s MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey, meaning it is difficult to determine the immediate local impact of addicts and their families telling their stories. Still, Superintendent Marco Rodrigues said in a presentation on the data that drug use rates among Hudson students are trending downward.

Though school committee members and teachers agree that is a positive sign, the school committee also agreed during that same presentation that the Hudson Public Schools must keep working until those rates reach zero.

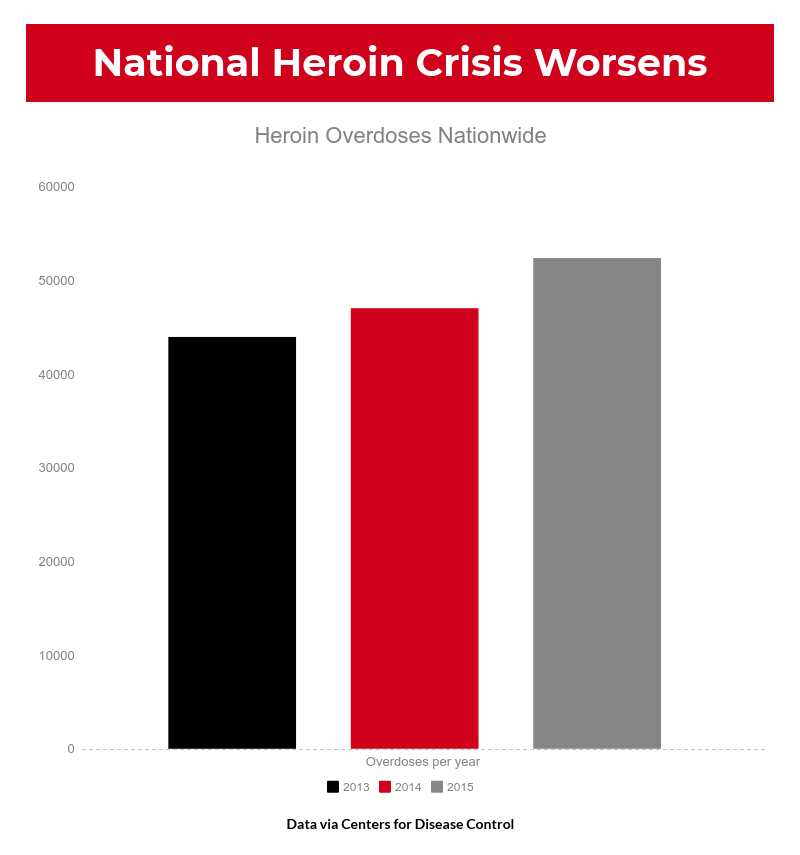

According to national data, that goal is a distant one. Last year, 64,000 people died from drug overdoses according to the New York Times, an increase of roughly 12,000 from just the year before.

Scott Tobin’s death earlier this year, unfortunately, made him the 13th Hudson resident since 2012 included in that year-end data, according to a Massachusetts Department of Health report. Thus, as she grieved, Nancy Tobin found a group of Hudson and Marlborough parents already grieving similar recent losses.

Kathy Leonard in Marlborough has spoken publicly about her loss as she planned the vigil Tobin helped with this year. Cheryl Juaire of Marlborough, who lost her son in 2011, actually formed an online support group of which Tobin is a member. And Erin Holmes, who lost her son in 2016, has also spoken publicly. She works with the Hudson Youth Substance Abuse Prevention Coalition to run events educating the community on the dangers of drug use.

Those are just a handful of the people affected personally by the opioid epidemic. In fact, the national community of grieving families and friends grows regularly as an overdose claims a new life every eight minutes, according to the 2016 data mentioned by the New York Times.

Though that is a community which, Tobin said, no one wants to join, it is also a community of people now eager to push through their grief and save lives by reaching into schools and other aspects of society.

“Something completely unfathomable has happened, and no matter how much I wish it to go away, it won’t,” Tobin said. “I just don’t want others to feel this. I just want to do something to help someone else with that big laugh that Scott had. I want that person to live.”

***

UPDATED: December 4, 2017 – 2:18 p.m.

There are programs and advocates available for those struggling with addiction and their loved ones.

MetroWest Hope meets on the second Wednesday of each month from 5:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. at First Church of Marlborough.

Addiction Referral Center (ARC) in Marlborough offers daily meetings and a drop-in center “to enjoy fellowship and a healing, healthy environment, where one can spend time with their peers.” They also offer referrals for treatment to those struggling with addiction or their families.

ARC also maintains a 24-hour emergency hotline (1-800-640-5432).

Learn to Cope meets weekly at 7:00 p.m. at the Hudson Senior Center. It provides support and education to families of those struggling with addiction. It also offers trainings in the use of Narcan, a drug that, when administered quickly, can reverse an opioid overdose.

Students struggling with addiction can also speak to their guidance counselor for support. Guidance Director Angie Flynn said that, while guidance would inform school nurses, administration and a student’s parents in such a case, a student would not be disciplined unless they violate Hudson’s substance use policy by carrying drugs on school grounds or attending school while high.

![Brazil's Neymar walks onto the pitch during his debut for Santos FC in a Sao Paulo league football match against Botafogo, in Santos, Brazil, Wednesday, February 5, 2025 [Andre Penner/AP]](https://bigredhawks.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Neymar-is-Back-e1743558992671.jpg)

Ms. Porter • Jan 26, 2018 at 5:09 pm

Interesting read. I think the article does a great job bringing in a variety of voices and angles. It would be nice to see what students who went to the presentations had to say too. The second bar graph is powerful. I know students who have spoke to me said the guest speakers really do make the topic more real for them, and that students who would often make a joke of the matter in class won’t with the speakers present. I fully support our health ed teachers in educating our student body on this important matter and as our guest speakers said breaking the fear and silence that has been associated with it.