by Dakota Antelman

By the time she was hospitalized after her second bout with self-harm last year, a current ninth grade student had already spent years struggling to access a complex and, at times, bureaucratic mental health care system.

The student did attend counseling immediately before and after she was discharged from the hospital. While those treatments were not the first she had received, it was the first time she had received care since she was much younger.

She saw a counselor when she was in fifth grade but had to stop when her family’s insurance plan switched from Blue Cross Blue Shield to Tufts, which her counselor did not accept. The student’s mother looked for a new therapist until things “seemed to sort themselves out,” and they stopped looking.

Nevertheless, the student would struggle with undiagnosed depression until eighth grade, only getting her diagnosis during her hospital stay.

While the student’s mother said she “should have done more” to get her daughter into treatment earlier, the struggles she faced in even locating that treatment have, in several cases, proven to be the result of widespread issues within the mental health care system that can lock certain teens out of treatment.

Some insurance companies load so much paperwork onto practices that counselors limit the number of plans they accept. Some counselors have no room in their schedules for new clients at times that fit with their daily lives. And families can even find it difficult to get in contact with counselors who either do not answer their phone calls or call back at times when they cannot answer the phone.

For teens like this current ninth grade student, the existence of these barriers can have grave consequences.

Getting Insurance to Pay

In accessing mental health care and getting it paid for, families either feast or face proverbial famine.

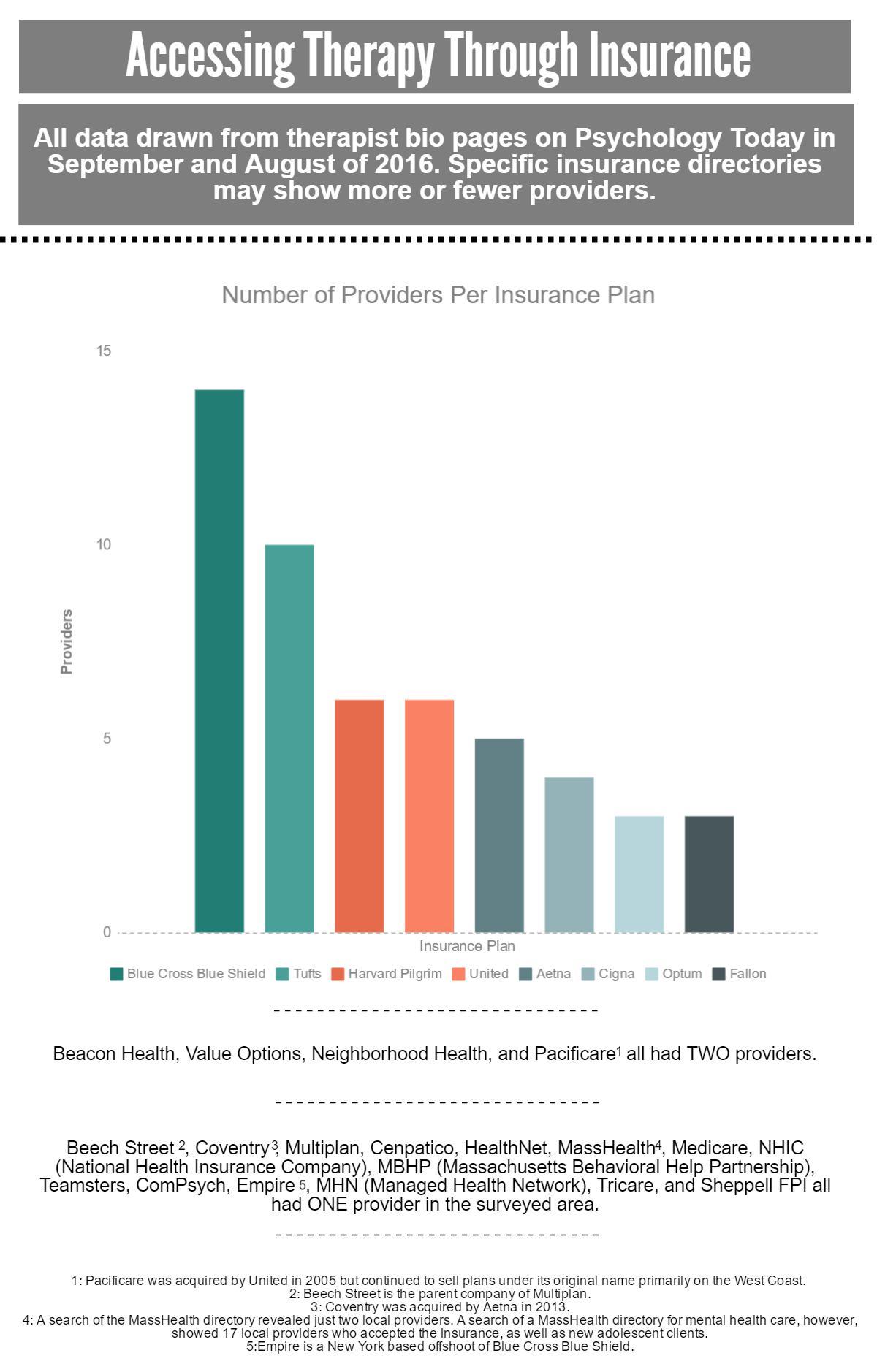

As part of a survey conducted in late September and early October, the Big Red contacted every counselor from Clinton, Sudbury, Marlboro, Stow and Hudson that was listed on a Psychology Today “find a doctor” database at the time. For those who did not respond to the Big Red, the publication used the insurance information provided by counselors in their biographies on the website.

The review of 24 local practices found only 15 who accepted any insurance. Of those, just nine accepted more than two plans.

A number of these practices also accepted the same plans meaning that, while some patients and their families might find it easy to get a therapist, others might find the process extremely difficult. A Blue Cross Blue Shield customer, for example, could choose from 14 local counselors that accept their plan and treat adolescents. Someone with Tufts as their insurance provider would have 10 to choose from according to the same database.

Other plans like Fallon Health, a Massachusetts-based health insurance, offered just three local practices who accepted adolescents at the time of the survey. Beacon Health, another Massachusetts-based health insurance, offered two at the time.

For clients with MassHealth, the state’s public health insurance program that expanded as more clients qualified for it under the Affordable Care Act of 2010, the search process can be complicated. There are 17 local counselors accepting new adolescent patients with MassHealth according to the “find a provider” page on the website of the Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership (MBHP). MBHP is the program which handles mental health care for MassHealth, and has its own website.

With the exception of two providers, however, none of these names were listed in the Psychology Today database, which is commonly used by teens and their families in their search for care. If someone on a MassHealth plan did not know where to look, they could have trouble finding care.

Kristen Morris, the mother of another HHS student who has sought mental health care, has observed these issues in trying to get her daughter into treatment.

Their family first started looking for a therapist while they were on a Blue Cross Blue Shield plan. They then switched to Harvard Pilgrim and saw their options narrow. When they switched to MassHealth, Morris said she found just two practices within 15 miles of Hudson that accepted her plan.

“I think that therapists not accepting health insurance is detrimental to people’s well-being,” she wrote in an email to the Big Red. “Once you’ve found someone that sounds like a good fit, it’s not a good feeling to hear that they don’t accept your insurance. It really cuts down on your options.”

Morris’s daughter has been to two different therapists since her family started searching for one when she was nine. Neither worked out for her, however, as she said she didn’t feel comfortable talking with them.

Kristen Morris wrote in the same email that she and her daughter have since decided to stop looking for therapy but will start again if her daughter sees the need.

Therapists Getting Insurances to Pay Them

The problems posed by insurance are nearly as frustrating for providers as they are for patients.

HHS school adjustment counselor Jaime Gravelle sympathizes with therapists who find the process of getting added to insurance panels arduous. Gravelle herself has experience working in residential treatment centers as a social worker and has dealt with the barriers to the mental health care system in her current job.

“There is a lot of red tape for reimbursements and for getting reasonable rates for services provided,” Gravelle said. “The amount of documentation for insurance panels is really extensive, and that can make it challenging for some practitioners to use a certain insurance.”

Several counselors contacted by the Big Red echoed Gravelle’s sentiments. They cited delays in getting reimbursed and low reimbursement rates as reasons to either limit the number of plans they accept or not accept insurance at all.

Brian Cohen, a Hudson-based therapist specializing in the treatment of ADHD, anxiety and mood disorders, listed those same reasons as central in his decision to not accept any insurance. He then went a step further, enumerating a list of other issues he has with the insurance industry.

Cohen explained that he does not like the fact that insurances periodically request copies of his notes for audit-like reviews of him and his patients. To Cohen, these reviews are an issue of patient confidentiality.

Furthermore, Cohen does not like the amount of unpaid time he would have to spend communicating with insurance companies to get reimbursements from them.

“I don’t have a problem talking to your school guidance department on the phone, your parents on the phone, or you on the phone,” he said. “But I do not like spending a half hour or an hour on the phone trying to get in contact with the insurance company and not get reimbursed [for that time].”

Cohen and other professionals in the field said that with public health care plans like MassHealth, these issues are only amplified.

“MassHealth wants to be able to regulate everything — how you’re writing the notes [or] how many sections you’re writing notes in,” Sudbury-based therapist Fred Gerhard said. “They want to regulate everything. That makes them harder to work with.”

A MassHealth representative contacted by the Big Red declined to comment on the record for this article.

The Big Red did determine, however, that MassHealth does require that its providers document in detail how they used time with their clients. This can involve curating a medical record including anything from progress notes to treatment plans. MassHealth also requires its providers to write their notes using language that non-medical professionals can understand. These notes come into play if MassHealth decides to review the records for signs of fraud or other illegal financial activities.

Nevertheless, for families who do not have the money to pay out of pocket for therapy, gaps in insurance coverage, either public or private, can hamper a person’s search for help from day one.

Few In-House Solutions

Mental illness is often triggered by a variety of stresses or incidents in a sufferer’s life. But in the adolescent population, the transition to high school can exacerbate underlying conditions, sometimes turning a manageable anxiety disorder in middle school into a more severe one in high school.

Knowing this, the Hudson Public Schools (HPS) have tried to offer their students coping mechanisms and outlets to address mental illness within their own schools. The high school wellness curriculum now includes units on stress management and mental illness. Some students also have the opportunity to attend Therapeutic Academic Support classes (TAS) where they learn coping and self-advocacy skills while boosting their self-esteem in a classroom environment. Additionally, the Hudson Public Schools have added another social worker like Gravelle at the high school as well as a school psychologist who visits all of the schools to offer help to students dealing with forms of mental illness.

Gravelle notes, however, that this in-house system has its limitations.

“If someone is coming in because they want to work through trauma issues, it wouldn’t be the most helpful thing for them to do that here in the school on a consistent basis and then afterwards have them be put back into the cafeteria where then they have to do lunch and take a math test,” Gravelle said. “It can be done and it doesn’t mean that within my office we never touch on those things, but I don’t think that it’s necessarily ethically in anyone’s best interest to do that in a school setting.”

Currently, Gravelle has 47 students on her caseload. Of those 47 students, she estimates that roughly half are already receiving outside counseling in addition to their meetings with her.

In connecting several of those students with their eventual outside help, Gravelle and her colleagues in the guidance department can take on the role of middlemen, providing students with names and information about local practices.

Indeed, when the Morris family looked for therapy for their then eighth grade daughter, that daughter went to the guidance department and asked for a list of counselors nearby. The department provided her with a list, and she saw a local therapist on that list for roughly two months.

However, that relationship did not work out because the student did not feel comfortable talking with the therapist. She stopped with her treatment and never came back to guidance to follow up.

The student said she still struggles with stress and forms of depression. While she said that she does think a therapist would alleviate some of these strains, she added that she is doing “all right” without one.

For Gravelle, Morris’s story highlights her need to communicate with parents about anything from insurance to issues of whether a student can build a personal connection with a therapist.

“I try to be very forthcoming and say, ‘This is the system. I recognize it has its faults. Here are some of the different ways that we can get your child support right now,’” she said.

When therapy does not work out as quickly as a student or a family might have hoped, Gravelle said she at least tries to provide a temporary solution to problems for which a student needs counseling — even if doing so in the school environment is not ideal.

“In my position it’s a lot of trying to keep up with that, checking in with people and asking, ‘Are you still interested?’” she said. “‘I know they said it will be a while, but can we do something in the school setting? Can I be that band-aid?’”

For many students, Gravelle has been or is that band-aid while they wait for outside help.

Getting Therapists to Pick up the Phone

In getting care outside of the school system, the first thing a student or their family must do is begin contacting counselors. But the length of that process can often vary based on how long counselors take to return a family’s calls.

For the unnamed ninth grade student mentioned earlier, that was just the case as her mom said she had to leave at least 15 messages with counselors before finally scheduling a session for her daughter prior to her hospitalization.

The therapists, many of whom either work in private practices or work in group agencies but manage their own phone calls, would often only call her back when she was at work and unable to talk with them.

“It’s terrible phone tag,” she explained, later concluding. “Trying to actually talk to someone, trying to find an appointment time that’s available on a regular basis that works with your schedule and their schedule is not easy.”

In this case, the student’s mother also feared for her daughter’s privacy when therapists’ answering machine messages asked that she leave a brief description of her reason for contacting them.

“You’re saying this personal information on this voicemail,” she said. “You have no idea who’s listening to it although you’re supposed to have confidence in the system that only the people who are supposed to hear it, hear it.”

For this reason, she would never leave her daughter’s name in the voice message when she called, instead waiting until the therapist called back to divulge that information.

This is an issue that can be exacerbated on public health care plans like MassHealth. Of the 17 providers identified through the search of the MBHP directory, five did not provide basic personal information like their name or gender in their biographies at the time of the search. In those cases, a patient seeking care could realistically be calling a phone number and only know the name of the practice with which a doctor is affiliated.

This family’s experience with therapists not returning their calls is also not unique. Even in reporting this article, roughly 75% of the local therapists contacted by email or phone did not respond to the Big Red’s first requests for information on their practice. They either missed the initial phone call or never replied to the initial email. In 38% of cases, therapists never responded to requests for comment despite two or three calls by the Big Red in the majority of cases.

Without Outpatient Care, Teens Turn to the Emergency Room

If and when someone calling a therapist is directed to leave a message on an answering machine, they would likely hear some form of the following instruction: “If this is an emergency, hang up the phone and either call 9-1-1 or go to your nearest emergency room.”

Indeed, when, for one reason or another, therapy is not available to someone with a mental illness, going to the emergency room is often their only choice.

But while there are emergency rooms near Hudson, with Marlboro Hospital situated just across town lines, the ways many of these emergency rooms process and treat mental health emergencies can put parents and patients in difficult situations.

Before she was admitted to a longer term inpatient center, the ninth grade student went to the emergency room twice in the span of two weeks after intentionally hurting herself. On the first occasion, emergency room staff told her family they would have to stay at the hospital for at least two more days if they wanted to get her into an inpatient program. She contracted for safety, and she and her family went home.

Two weeks later, back in the ER and faced with a similar choice, her family decided to keep her at the hospital and have her admitted to the inpatient center.

“That time I wasn’t taking her home again; I was too scared,” the student’s mother said. “The first time I was torn between ‘Does she really need inpatient care?’ The second time I was like, ‘She needs it. It’s going to be the best thing for her.’ So we insisted that she get admitted.”

The student spent a week in the inpatient center. There she said she learned coping skills that have aided her in her struggles with depression in the months since she was discharged. Insurance also covered the financial costs of her hospitalization, saving her family from treatment costs that can soar past $2,000 per day according to a Becker Hospital review of state-by-state inpatient care costs done in 2013.

But buried in those two emergency room visits was an unavoidable fee that frustrated this student’s mother.

While they initially went to the Emerson Hospital emergency room, the only hospital their insurance would cover at the time was Cambridge Hospital. To get there, they would have to drive 30 minutes from Concord where Emerson Hospital is located to the Cambridge hospital campus in Cambridge. Once they were admitted to Emerson, however, hospital regulations did not allow the family to travel to Cambridge on their own. They had to take an ambulance between the hospitals and subsequently had to pay the bill.

“The only real charge was the ambulance fee, which to me isn’t fair because it’s required,” the mother said. “There’s no choice.”

But while this family did have to pay the ambulance bill, and did face the tough decision of possibly waiting days for a bed in a long-term facility to open up, they avoided some of the other problems that plague emergency rooms.

The wait time for beds in psychiatric hospitals can sometimes be longer than two days. Much of this is due to the decrease in beds statewide, as reported by PBS Newshour in September.

The report revealed that, between 1990 and 2014, the number of beds designated for psychiatric patients had plummeted from 102,307 to 37,450 beds.

That waiting game for a long-term bed can only start, however, once a patient sees a doctor in the emergency room. Gravelle said that even this can often take hours.

“To sit in an emergency room for 10 hours [or] 12 hours to be seen by a clinician to assess you if you’re feeling suicidal, that’s typical, and it is not at all the best treatment for anyone,” she said. “Everyone agrees on that, but the question is, how do we fix it?”

Waiting for just an hour before being seen by a nurse, and seeing a doctor within a half hour of that, the mother of the ninth grade student knows that her family was able to avoid the worst of ER gridlock.

“I used to work in an ER, and part of it just depends on the type of care you need and the volume at that moment,” she said. “We probably just hit some good times in terms of not a long wait.”

Finally, the ninth grade student’s family was able to stay with her, supporting her and keeping her safe while she waited for treatment. For many adults or older adolescents who go to the emergency room alone with suicidal thoughts, a wait for care of any length can be much harder.

Busy Lives Mean Fewer Choices

Even if an adolescent never needs treatment in the emergency room, if their insurance has a variety of therapists on it and if therapists do return their family’s calls, an adolescent in need of mental health care still might have more barriers to work through before they even get in the door of an office.

Therapists, like most other professionals, work during the week. While some offer evening hours and, in some cases, Saturday hours, the bulk of their sessions occur while students are at school. This means that students would not necessarily be able to just choose from the practices that accept their insurance.

Unless they get dismissed from school, a HHS student can only see a counselor after 2:03 p.m. Since only two counselors in Hudson replied with openings in their schedule, one of which was Cohen who accepts no insurance, a student who needs insurance to pay for their counseling would likely need to expand their search outside of their hometown. With working parents, a student could then realistically see his or her options for counseling narrowed to the hours after 5:00 p.m. and still have to deal with the other barriers against getting care.

Such was the case for junior Elizabeth Cautela. Cautela began seeking a therapist last December to treat depression and stress that she was dealing with at the time. When her mother first called local practices, no offices in Hudson had times available for her that fit with Cautela’s varsity and club sports schedules and the schedules of Cautela’s parents, both of whom have full-time day jobs.

One of the therapists Cautela’s mother called did direct her, however, to a colleague that the therapist believed practiced in Marlboro and might have had room for Cautela. The therapist did have room, but she did not practice in Marlboro. Instead, she practiced in Framingham.

Tired of searching, Cautela and her family booked bimonthly sessions with the Framingham therapist.

While she said her therapist has helped her, the 35-minute, one-way commute to her appointments has been difficult for Cautela. Even though she got her driver’s license earlier this year, she does not have access to a car until her mother returns from work. This means she can only see her therapist in the evenings during the week, narrowing her options for the timing of sessions.

But the car is not her only scheduling constraint. During the fall, Cautela was unable to see her therapist at all. Her field hockey practice did not end until 5:30 p.m. each evening. Her therapist’s last regular session started just 30 minutes later, at 6:00 p.m. There would not have been any way for her to get from practice to her therapist before she closed for the day. So, even after finding help, Cautela could not access it as she made the stressful transition to junior year.

“Junior year has been the roughest year of my life; it really has been,” she said. “I’m stuck because I can choose sports, or I can choose therapy. But, if anything, sports cause me more stress because the culture is so intense — if you’re not winning, you’re doing something wrong. So I’m more stressed during sports season, but I don’t have the time to get to the therapist in the first place.”

Debora Franco, a Marlboro-based therapist who treats adolescents, is aware of the problems teens like Cautela encounter with travel times and therapy schedules. She wrote in an email in September that she normally sees teens between 3:00 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. and does, from time to time, offer weekend hours. She added, however, that those openings “might not be [on] the days and [at the] times that teenagers or their parents are available to come for an appointment.”

Elisa Sweig, another Marlboro-based therapist, echoed Franco’s statements in a similar email, writing that her accessibility is dependent on her schedule at a given time. Her patients can also be dependent on their parents to bring them to appointments, limiting openings in their own schedules.

For Cautela, her counseling has been a positive experience. She has been lucky that she has accessed it and is glad to have found a therapist with whom she can have honest conversations. The same cannot be said for many of the students interviewed for this article.

But still, she wishes things were different — both for her and for her classmates.

“I wish she was here in Hudson or the therapists in Hudson had more room because I think it is sort of ridiculous that I have to go 35 minutes to get to my therapist,” Cautela said. “It’s needed, and it’s necessary for kids my age and kids in high school in general. They need to get to a therapist, and when they can’t get to a therapist, what do you do?”

The Response

Teens, their parents, and their care providers often find themselves trapped by the government’s approach to certain aspects of the mental health care system.

Social workers can be so bogged down by the problems within the system that they do not return a prospective patient’s calls.

In what Brian Cohen labeled a “bureaucracy,” public health insurance plans demand profuse documentation of services provided. This can push providers off insurance panels, an action that can inadvertently close their doors to lower income teens and their families.

Emergency rooms can, at times, lack the space or staffing to treat patients promptly.

Inpatient centers can be even worse, with prospective patients sometimes waiting days for beds to open up.

In 2010, the federal government attempted to address the insurance barriers by passing the Affordable Care Act (ACA). While that act did increase the amount of people on health insurance, it did not completely eliminate the aforementioned bureaucracies that still limit the effectiveness of public plans like MassHealth.

On a more local level, the 2007 decision in the Rosie D v. Romney lawsuit brought attention to issues with mental health care in Massachusetts and prompted the creation of the Massachusetts Childhood Behavioral Health Initiative (CBHI), among other things. Under the CBHI, the state has worked to increase access to in-home treatments for children with “significant behavioral, emotional and mental health needs” according to the initiative’s page on the Massachusetts Health and Human Services website.

Most recently, the state has tried to deal with these problems through a series of bills proposed in the Massachusetts State Senate and House of Representatives.

For any of these bills to become a Massachusetts state law, they would most likely need to pass through the Joint Committee on Mental Health and Substance Abuse. This committee is made up of six state senators and 11 state representatives and is tasked with reviewing proposed laws regarding drug abuse and mental health.

Since January of last year, the committee has reviewed at least seven pieces of legislation addressing access to mental health care for teens in some way. These proposed bills seek to improve issues ranging from emergency room efficiency to MassHealth coverage. The first batch was referred to the committee on January 20, 2015, while the second was sent to the committee on April 15, 2015. These bills have since circulated through a series of committees, and all now sit in either the Senate or House Committee on Rules attached to a series of study orders from their respective branch of the state legislature according to the Massachusetts Legislature website.

Jaime Eldridge, the state senator representing Hudson and its surrounding towns who also serves on the joint committee for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Awareness, did not comment on these bills or the issues described in this article despite multiple requests from the Big Red.

As a result, the Big Red can only provide information on the bills based off their descriptions on the Massachusetts Legislature website.

This series of bills did include two that addressed issues with MassHealth. One, H.1805, advocated for “equitable access to behavioral health services for MassHealth consumers,” while another, H.1812, added “affordability” to H.1805 while mirroring much of the rest of the bill.

Two other bills dealt with forms of inpatient care with one bill, S.1027, requiring health care coverage for patients visiting ERs with psychiatric issues and another, S.1028, seeking to decrease wait times for inpatient care.

The remaining three bills all sought to improve access to mental health care as well but overlapped in several areas with other bills.

Stuck Behind the Barriers

Every year, teachers and guidance counselors tell students to reach out to get help if they are suffering from mental illness. Yet in many cases, those who try to find help don’t get it.

For Gravelle, who tries to fight through these barriers to the mental health care system on behalf of her students, this system is broken.

“When someone is in that place where they’re open to help, we want to move on something quickly,” she said in an interview earlier this year. “But the system isn’t there to provide that immediately, and I think that’s a huge obstacle. That’s where I think it’s a public health issue of how do we make it possible for people to get the help they need?”

For Cautela, who has battled anxiety and depression as a teen, getting counseling is crucial. Unfortunately, for many teens, there is no way to get that counseling but through the system that can and has shut out many of their classmates and friends.

“Without any guidance at all of how to deal with this stress, you’re stuck wondering, ‘What do I do?’” she said. “You don’t know how to handle it. It consumes you. You don’t know if there’s a way out because it feels like it is all building up on you, and you don’t know how to relieve it.”

Students often know that help exists. They are often aware of the solutions that may lie within their grasp if the system were more streamlined. But, like Gravelle, they say that that system is broken. And, they add, it is in need of fixing.

“Everyone agrees on that,” Gravelle said, speaking on the subject of emergency room inefficiency in particular. “But the question is, how do we fix it?”

***

This article’s feature photo was a collage of headlines from major media outlets discussing the mental health care system. The headlines used were “Report: Mental Health Care Still Relatively Difficult to Access” by Peter Biello NHPR, “Young Adolescents as Likely to Die From Suicide as From Traffic Accidents” by Sabrina Tavernise of the New York Times, “Community Mental Health in Massachusetts: Disturbing gaps in care and safety” by Maggie Mulvihill of the Eye and “Which Americans Are Shut Out of the Affordable Care Act?” by Teresa Mears of US News.

This article is the third in an ongoing series on mental illness among adolescents and young children in the Hudson area. To read part one, exploring academic stress among K-7 HPS students, click here. To read part two, exploring the link between mental illness and academic pressures for high school students, click here.

If you have suggestions for additional articles or tips regarding this article in particular, please contact us through this form.

![Brazil's Neymar walks onto the pitch during his debut for Santos FC in a Sao Paulo league football match against Botafogo, in Santos, Brazil, Wednesday, February 5, 2025 [Andre Penner/AP]](https://bigredhawks.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Neymar-is-Back-e1743558992671.jpg)

Lynda Chilton • Dec 14, 2016 at 2:10 am

Great article Dakota! Kudos to you and The Big Red for bringing up important issues that are helpful in starting a dialogue in our school and community.