by Rachel McComiskey

Two years ago, approximately 68 percent of students said a huge part of their stress comes from school. Reports of self injury have increased by about four percent, and suicidal thoughts have increased from 10.5 percent in 2010 to 14 percent in 2014.

These stats came from the 2014 MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey. Administrators use the survey data as evidence when looking to add personnel or new wellness units to address the harshest revelations from the survey.

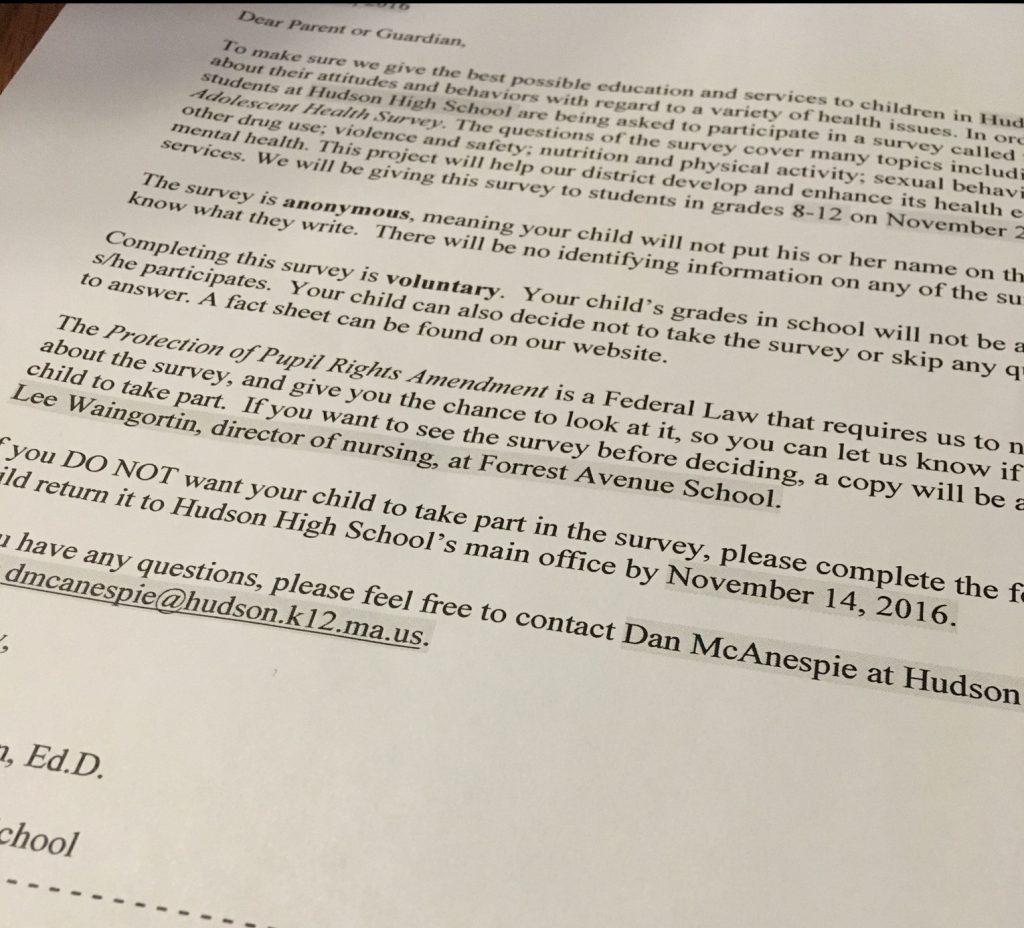

Students in grades 6-12 take the survey every other year. Students at the high school just completed the survey on November 22. The survey asks questions about substance use, mental health, bullying, and general health and nutrition. For students in grades 9-12, there are also questions about sexual behaviors. It’s anonymous and voluntary. The main office sends a notice home about a month in advance, so parents are aware of it and can send a part of the notice back to the school asking for their child not to participate in the survey.

In the beginning of the 2011-12 school year, the school hired Jamie Gravelle, the school adjustment counselor, and, this summer, a second school psychologist joined the guidance department. Special education teachers have been added to the therapeutic academic support class, as well, as a result of the survey data.

In the past few years, the wellness teachers have been altering their classes to include more visits in class from the guidance counselors. Since 2011, guidance and wellness teachers have increased the programming around mental health, adding presentations like “Break Free From Depression” in the ninth grade and “Stress and Anxiety” in the eighth grade.

“Those [units] are typically about raising awareness,” Jamie Gravelle, the school adjustment counselor, said. “Helping students to know what the signs, symptoms, resources, [and] the coping skills people can utilize are. For me, it’s really about decreasing stigma [and] normalizing that there’s a pretty high percentage of the population who experiences stress, anxiety, or depression. It happens a lot, and by talking about it in classrooms and normalizing it, it makes it easier for people to get help.”

A ninth grade student, who requested for her name not to be used, has noticed the shift to focusing on mental health and substance abuse in health classes.

“I feel as if it’s important [to talk about] because there are so many people struggling with depression and harming themselves, as well as drinking alcohol and smoking weed,” she said. “I feel like letting people know [the consequences of] doing those things is good. So [when students and their parents] look back [they can’t] say, ‘Wow, it’s the school’s fault for my drug abuse [because they never taught me about it]’ or ‘The school never taught students to [talk to an adult if they know] people who are struggling with depression’ or ‘Wow, nobody taught me about depression. I could’ve done something, but now it’s too late.’”

In addition to the increase in mental health units, the wellness teachers altered the substance abuse curriculums. In 2014, administration noticed an uptick in alcohol abuse.

“To be honest, it wasn’t that we weren’t paying attention to it, didn’t see it as important,” Gravelle said. “I think there had been so much shift to focusing on opioids and marijuana that we had spent less time talking about alcohol. So the data [pointed out] that [alcohol use needed] to continue being a potential concern.”

Junior Spencer Cullen has seen the negative effects of substance abuse on school and the personalities of people he knows. However, he doesn’t think those problems have been addressed very well.

“[I think] more of an upfront and personal stance [would influence students more],” Cullen said. “[Right now] it’s very textbook [based] and not personal.”

Beyond the school system itself, educators have also sought outside help to take action on the survey results.

Using the data, Hudson applies for grants, such as the Hudson Youth Substance Abuse Prevention Coalition. The coalition will help facilitate and implement strategies and activities in Hudson High School and Quinn Middle School. Strategies include supporting the addition of new wellness courses, supporting efforts to increase screening for youth substance use, prevention, intervention, and referrals to treatment.

“It’s not data we just do to get it and then just throw it into a filing cabinet somewhere,” Principal Brian Reagan said. “It’s actually used.”