by Dakota Antelman

It took over a week to schedule an interview with Harvard-bound senior Scott Kall. With three impending AP exams and a long list of prior commitments, Kall’s schedule was packed.

We had to, on multiple occasions, reschedule meetings because a rehearsal ran long, or because he remembered an urgent meeting he had to attend.

Finally, I received a text at one o’clock on a Monday morning. Scott said he would be available for an interview that afternoon.

When I spoke to him 14 hours later, Scott said he was tired. He had gone to bed just after sending that text at one o’clock that morning. That, however, was what he described as a “good night” of sleep.

Kall was one of many students in Hudson High School who spent hours on homework and extracurricular activities, pushing for a bright college and professional future, but inadvertently compromising parts of their mental health.

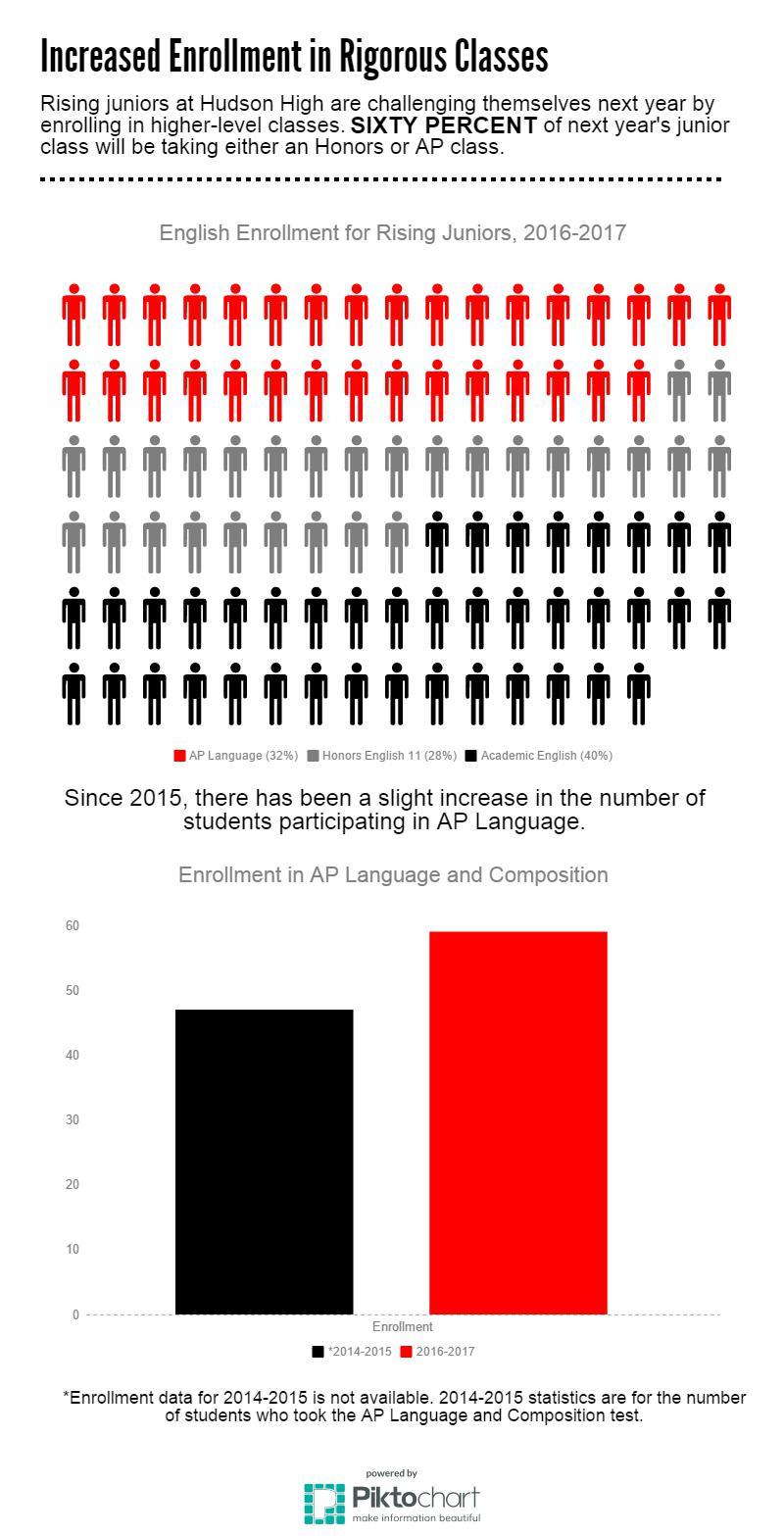

With higher standards for public education than ever before, colleges are raising their own standards, demanding more and more of their applicants. A College Board report on trends in college education this year found that tuition for public and private colleges has increased by close to 50% since 2000. Likewise, the average acceptance rates to public colleges have plummeted with the UMASS Amherst acceptance rate falling from 71% in 2001 to 53%, according to the university’s annual fall reports.

These factors mean that the pressure is on for students who want to earn a spot in their dream college. This pressure has made it so that, for these students, sleep deprivation, isolation, and, in some cases, self-hate, are daily battles.

The Drive to Succeed

Hudson High School students in all grade levels are urged at the beginning of each school year to pay attention to their grades. Especially in ninth and tenth grade, administrators remind students that their grades are now added to their transcript.

For freshman Holly Kerr, this direct link to her college future has created stress over how each individual grade she earns will affect her career.

Kerr wants to go to college for criminal justice. She has felt this way since she was five years old. In high school though, she has encountered stress about fulfilling this dream.

“For some people, this stress really does start freshman year, and for me, it really does build up,” Kerr says. “I feel like if you work that hard and do stress about it, it can be a good thing in some cases, but in other cases it just is not healthy at all.”

Kerr says her stress about her transcript, her grades, and her future in college is most notable in relation to tests. As she has entered high school, Kerr has experienced panic attacks and stress centered around tests.

“I have that thinking like ‘This is important for college,’ and with that anxiety, I also think that I’m going to fail,” Kerr says. “Last year, it got really bad for some reason, and I don’t know why. I would take the test, I would feel confident for like two seconds, and then I couldn’t even stay in the room. I would have a special pass to go to guidance and just take a break and stay out of that room because I was so stressed.”

Kerr says that the fix was only temporary and notes that she still faces similar symptoms of stress as a freshman.

Freshman Julia DeFreitas sympathizes with Kerr. After getting straight As through eighth grade, DeFreitas has felt intense anxiety as her ninth grade classes have proven far harder to earn an A in.

“After making Horace Mann every single term [through eighth grade], I thought that it felt really good to get great grades. But at the same time because I got those grades, it is kind of overwhelming now [trying to maintain them,]” DeFreitas explains. “There’s no point in stopping now, since I worked so hard; so I don’t stop.”

DeFreitas explains that because of what is already on her transcript–all honors classes in ninth grade–she feels locked on an academic track that will continue to place her in honors and, eventually, multiple AP classes, despite being overwhelmed.

“I’ve always been doing these hard classes,” she says. “I don’t want it on my transcript as ‘She was doing an honors class here in freshman year and dropped levels in sophomore year.’ I don’t want them [colleges] to ask ‘why?’”

Beyond schoolwork, DeFreitas participates in a variety of extracurricular activities. She plays volleyball during the fall and runs unified track in the spring. DeFreitas is also part of the National Junior Honor Society, a group that honors students who maintain a 90% average in their classes and participate in community service initiatives outside of school.

However, she adds that if it would not cost her in the college application process, she would consider not participating in high school sports. She says that she would rather “focus on my studies.”

Elizabeth Cautela recounts a guidance presentation on course offerings in eighth grade. She notes how AP classes quickly became goals for her. | by Dakota Antelman

DeFreitas is not alone. Elizabeth Cautela, a sophomore, suffers sleepless nights and moments where she says she shakes with anxiety over whether she will get into her college of choice.

“Ever since I was young, I was always told by teachers, ‘You have to try your hardest, or you won’t get into college.’ That’s been drilled inside of me since elementary school,” Cautela explains. “It’s been years and years of building up.”

Cautela is, like DeFreitas, a member of the National Junior Honor Society. She has spent two years as a goalie for the girls varsity hockey team, and she spent this past fall as the starting goalie for the varsity field hockey team. She feels pressure to build up a strong resume as she pursues admission into Emerson College.

She fell in love with Emerson College during her freshman year and sees that school as an ideal place for her socially and academically. However, her love for the school has quickly taken on a stressful edge as she says she feels daily pressure to maintain the GPA she needs to be accepted.

“Every day I’m thinking about college,” she says. “Sometimes I don’t sleep at night because I’m thinking about college. I think about what happens if I don’t get into Emerson or NYU or one of my dream schools? What if I get into college, and I don’t get a job afterwards?”

Her fears about getting a job are not without reason. In an article published last June, Newsweek reported that the number of employed new college graduates has fallen by 12% since 2000, plummeting from 84% employment in 2000 to 72% in 2012. While the nationwide unemployment rate has been hovering near 5% since October of 2014, the unemployment rate for new college grads has soared to 13.8%.

Eyeing her future, Cautela says she views even a B+ grade on her transcript as a “stain” that she must remove at any cost.

As student’s age, however, the costs become greater.

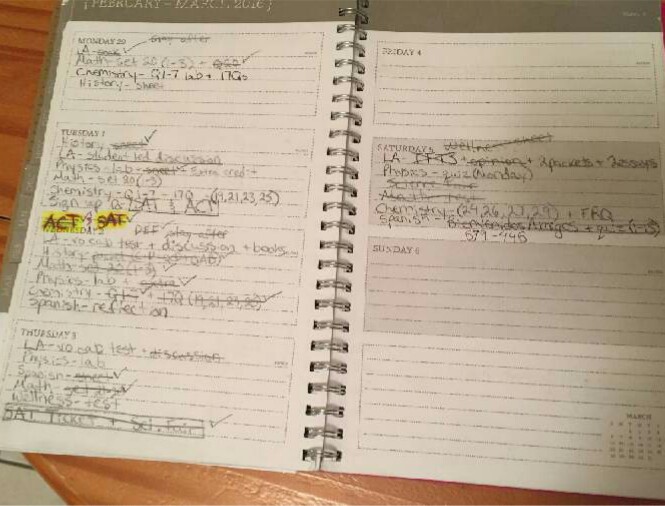

Sam Joubran says that, as a junior, she has felt physically sick when she is worrying about grades. She also now has close to no free time, telling The Big Red, in an interview on March 17, that she had mapped out her activities down to the hour all the way through May 20.

“There’s a lot of pressure to have the academics on top of community service and the extracurricular [activities],” Joubran says. “You have to pretty much be as busy as humanly possible and still get the best grades as possible.”

Often, however, that goal is an unattainable one. In an attempt to accommodate their schoolwork, students sometimes scale back their extracurricular activities.This becomes problematic when these activities provide relief from stress. Caleb Brush has experienced this issue during his sophomore year.

The night before an interview in late April, Brush had so much homework from his AP Biology class that he needed to skip his basketball practice, something he says he never does.

But basketball is not the only sacrifice Brush has made.

“I love to play guitar, and that’s something that gets harmed by the amount of work I have,” Brush says. “It’s just something that helps me relax from the stress, and when I can’t do that because of work, the stress just builds. That’s when I start losing sleep.”

Scott Kall explains that maintaining his high grades cost him parts of his relationship with his own family. His participation in Drama Society in particular kept him at school until 7:00 pm for months out of the school year. He says that once he would leave school for the day, he barely had time to eat dinner with his family before “locking” himself in his room and doing up to six hours of homework.

“I feel so bad,” he said. “I love my family dearly, and I hate that that’s the way it has to be. But for me, that’s the way it has to work.”

Students Pay the Cost of Stress in Sleep

The majority of students interviewed for this article see doing as much as possible and still getting good grades as a task for which there are too few hours in the day. Beyond a lack of downtime and connection with friends and family, sleep deprivation is a rampant problem for Hudson’s high achieving students.

Though the Centers for Disease Control recommends that teenagers should get between nine and ten hours of sleep per night, Kall says he regularly sees a parade of Snapchat posts from classmates still doing homework at 3:00 am.

Kall himself says that, during senior year, he would go to sleep between midnight and 1:00 am. Last year, he says that the sleep deprivation was worse. He would consistently go to bed after 2:00 am during his junior year. When his extracurricular activities demanded more of his time, or when he needed to study for the series of finals and AP exams that coincided with the end of the school year, Kall says he often stayed up past 3:00 am.

Amidst nightly marathons of homework that he says could last up to six hours, Kall found himself “fading out.”

“Sometimes I will just look at my computer screen and totally blank out,” he says. “[I think] ‘I don’t even know if I can do this.’ Eventually I push past it, and it subsides.”

Caleb Brush, who is currently enrolled in AP Biology, finds himself tired during the school day due to lack of sleep. Brush explains that AP Biology itself has added more than an hour to the amount of time it takes for him to get his homework done each night. Partially because of this, he says he gets between four and six hours of sleep on a daily basis. For Brush, the lack of sleep increases the stress he deals with.

“Staying awake in class is difficult. Paying attention in class is difficult,” he says. “It harms my performance in school. If I have less sleep, I do worse than I’d like to do in school. Then I feel stressed. The stress just builds and builds and builds.”

Even freshman Julia DeFreitas says that during her volleyball season, she would often find herself getting between four and five hours of sleep per night. Like Brush, she ties her lack of sleep to at times poor performance in school.

“It’s not great [when I can’t get enough sleep],” DeFreitas says. “You’re in a bad mood. You’re rude to everyone around you. You don’t want to be that person. It’s kind of just waiting for the weekend [to sleep].”

But even the weekends bring stress and sleep issues.

“On Saturdays and Sundays I want to sleep in until noon. But I can’t really do that because I have to get up and do homework for Monday,” DeFreitas says.

Other students like Sam Joubran and sophomore Sam McLaughlin are able to get to sleep earlier. Joubran says that she has managed to still sleep close to seven hours per night during her junior year. McLaughlin, who runs for the cross country and track teams after school almost all year, while also participating in UNICEF Club and serving at a soup kitchen weekly, says she gets eight hours of sleep on most nights.

Joubran and McLaughlin are a minority in Hudson High School. According to the MetroWest Health Survey, only 31% of students get eight hours of sleep per night, leaving the other 69% susceptible to the effects of sleep deprivation. The CDC has repeatedly reinforced its guidelines with studies on sleep and its effect on the body. They conclude that not getting enough sleep can exacerbate depression and lower the overall quality of life for a person.

Sleep deprivation, and the overloading of homework that can cause it, is an issue which local schools have sought to address. A Boston Globe report published in March focused on one such school, Nauset High School, that pushed its start time from 7:25 to 8:35 in 2012. Nauset had students with similar patterns of sleep deprivation prior to 2012. Tardiness had been high, and many of its students reported effectively sleepwalking through early classes. The Globe stated, however, that once the start time was pushed back, grades in Nauset improved, and tardiness dropped by close to 50%.

Closer to Hudson, the Newton Public School system has taken a different approach to dealing with sleep deprivation and stress in general. After a trio of student suicides there over the course of four months during the 2012-2013 school year, the school district and the community reacted quickly. By the beginning of the 2013-2014 school year, Newton had instituted rules allowing students to reschedule tests when they had more than two on the same day. Newton also added select homework-free weekends and vacations designed to give students a break from homework and allow them to catch up on sleep.

In an interview conducted in March, Hudson High School Principal Brian Reagan said that he had not considered implementing policies similar to those introduced in Newton.

“I have had it come up with parents who ask about rescheduling tests. Parents are always asking if there’s a way to coordinate when kids have tests,” he said of Newton’s policies. “If you think about it, technically, no, everybody has different teachers at different times. It’s almost impossible for a teacher to pick a test on a day when all 25 of her kids don’t have something that day. The idea is pretty intriguing though.”

For Kall, who graduated this month, any changes will be too late. Reflecting on the struggle for sleep that he and his classmates deal with, Kall notes a “soldiers in the trenches” kind of bonding that he and his classmates feel after spending months without enough sleep. He says he feels like, at least in terms of sleep deprivation, he is understood by his classmates and, to some extent, his teachers.

“Every day in Spanish Mr. Sacco asks us how many hours we slept last night. We’re all like ‘four, five, six, seven and a half, four, three, three and a half,’” Kall says. “His eyes are just bulging because he thinks it’s so crazy. That’s funny because a lot of people do understand this, but at the same time for so many reasons we have to stay up.”

Hudson’s Attempts to Battle Student Stress

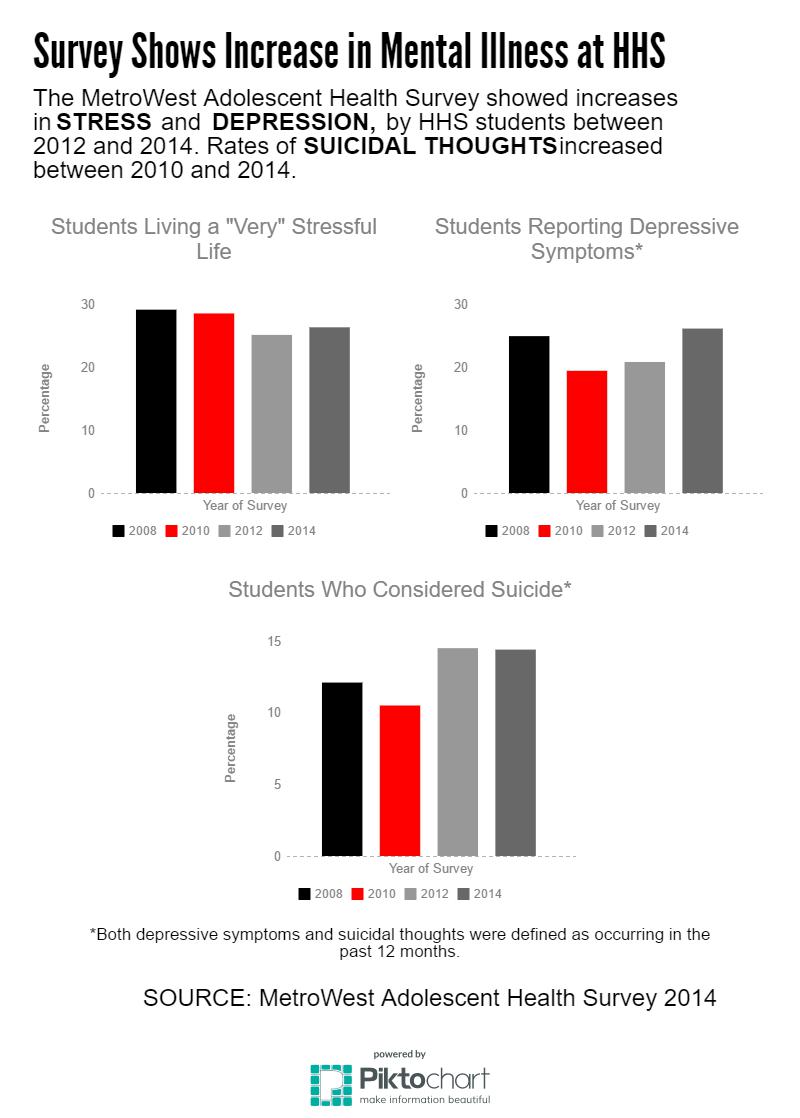

According to the MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey in 2014, one in three Hudson High School students report living a “very stressful life.” Of those students, 68% cite schoolwork and grades as the main source of their stress.

Hudson teachers and administrators see these figures as problematic but have struggled to find methods to reverse them. Budget problems, state testing benchmarks, and the inherently slow nature of “policy change,” in particular have left administrators in Hudson with little to work with in regards to mental health.

Jamie Gravelle, the licensed social worker for Hudson High School says it is difficult to even find time to meet with students in need of mental health counseling. She works in the school building from 7:30 am until shortly after school ends at 2 pm. Students are allowed to schedule appointments to speak with Gravelle during the school day but often do not want to. Without open time in Hudson’s class schedule, accessing mental health services from the school can cost students classroom time. In some situations, this means that seeking help can worsen the problem a student needs help with.

“I will try to work with students recognizing the fact that to take them out of an AP stats class because they’re stressed about the workload makes the stress worse,” Gravelle says.

Gravelle’s caseload has also increased substantially in the five years since she was hired. In an email to the Big Red in May, Gravelle said that, at any given time, she is meeting with between 35-40 students every week. She added that she has relationships with up to 20 other students who meet with her “as needed.”

Gravelle’s caseload is so large in part because of budget cuts last June. Facing a $750,000 shortfall, the Hudson Public Schools slashed funding for a full-time clinical psychologist. This year, therapeutic academic support teachers, Gravelle, and a part-time psychologist contracted by the school have absorbed the increased number of students in need of counseling.

Hudson Public Schools Superintendent Dr. Jodi Fortuna admits that the situation has not been ideal, saying that Gravelle is “stretched to the max.” Heading into next year, Fortuna hopes to alleviate some of the strain placed on the guidance department by adding a second social worker at the high school as well as a clinical psychologist to service the entire school district.

“Hopefully we’ll be able to keep those in [the budget] because I look at them as essential pieces,” Fortuna said of the positions in an interview in March. “We only asked for additional funding this year for positions that were essential, and these two positions we really felt were essential for our students.”

Recently, Fortuna confirmed that the requested positions will in fact be added for the 2016-2017 school year.

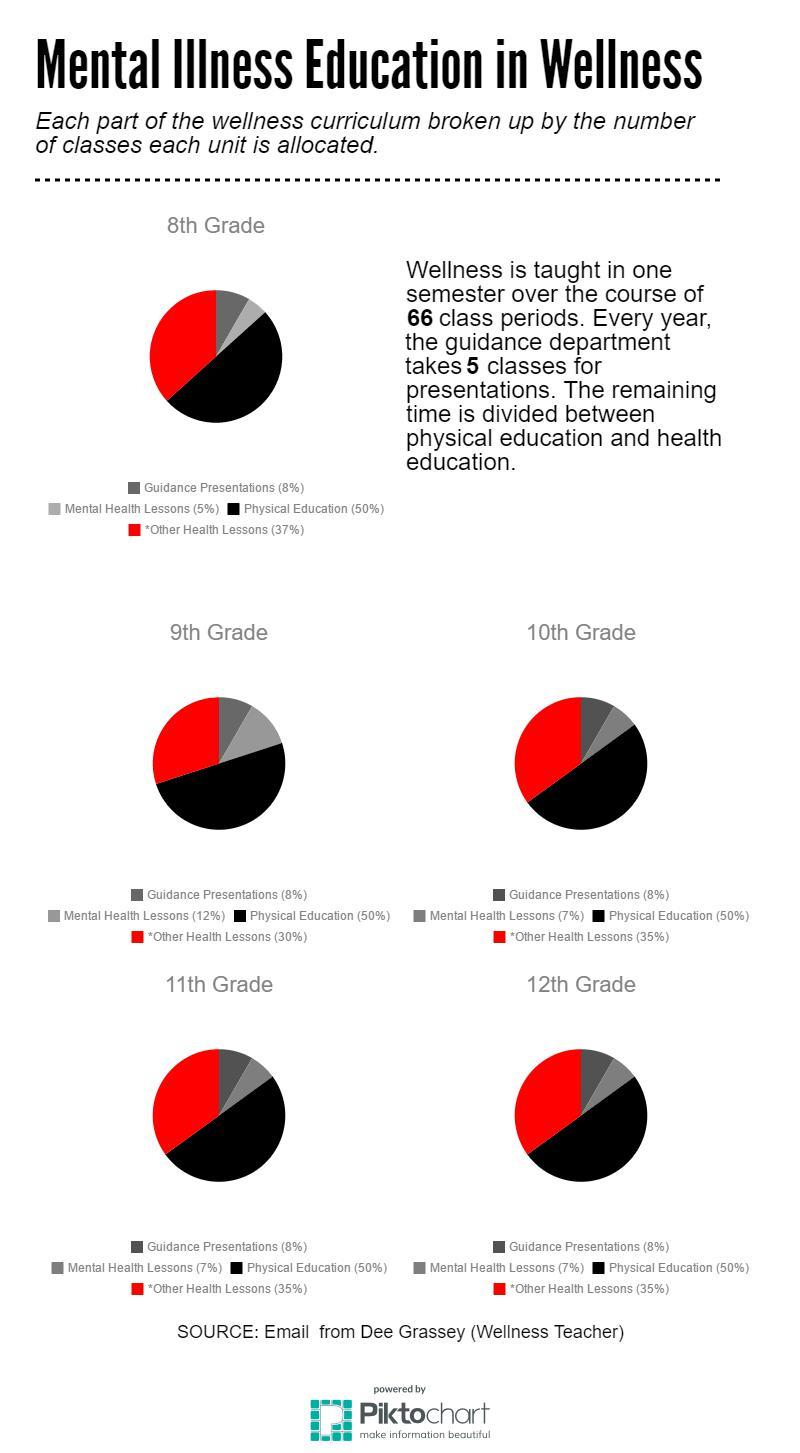

In the meantime, Hudson Public Schools have looked for solutions inside the classroom. Hudson is now in the third year of a new schedule that, when it was introduced in 2013, made four semesters of wellness classes a graduation requirement. This class, which students take for one semester of each year of high school, is a hybrid of physical education and health education. Its health portion, which is taught over six weeks, has slowly incorporated more and more programs addressing mental health since 2013.

Currently, the curriculum includes at least one unit per year on either mental illness or some form of stress reduction. The programs used range from the Break Free From Depression unit taught in ninth grade to a specific stress reduction unit taught in twelfth grade.

Though Wellness Curriculum Director Jeannie Graffeo believes that Hudson is “doing pretty well,” she, Gravelle, and Hudson’s own students agree that the current curriculum is still not enough.

“We would love to offer more,” Graffeo says. “In this time frame, we try to cover what we can, and we try to prioritize what [units] we have to based off of the national guidelines and also based off of what we’re getting locally.”

Gravelle believes that the accelerated mental health classes do serve a purpose–as a jumping off point.

“I’ll be the last to say that a couple classes is going to be the end all be all for this,” she says. “But for me in inserting these moments, we’re acknowledging it. We’re validating it.”

While some students like Elizabeth Cautela say these programs did little to ease their stress, the Break Free From Depression unit, as well as a stress reduction unit taught in eighth grade, have managed to identify students in serious need of help.

The stress and anxiety unit has been taught to eighth grade students in semesters one and two of this year. From those two sets of students, the program referred 14 to their guidance counselors for counseling outside of the wellness classroom.

Data on referrals from Break Free From Depression is not available. Nevertheless, a final assessment at the end of the course this year indicated that 64% of the ninth graders would seek help from friends or staff if they found themselves suffering from mental illness.

Gravelle hopes that as the wellness curriculum continues to evolve, and, as new positions are added within the guidance department, that more students will seek help.

“I do think there are more students who aren’t even identified yet who would benefit from some kind of support,” Gravelle says. “My ultimate goal as a therapist is to see utilizing counseling support as preventative like getting your teeth cleaned. We don’t wait until our teeth are falling out of our heads to go to the dentist.”

Outside of the wellness lessons, Gravelle and wellness teachers like Graffeo seek to integrate the stress reduction methods they are teaching into the rest of the school.

“I’ve always said to my colleagues, ‘We are the experts,’” says Graffeo. “We need to get out, and we need to help other teachers in our building. We should share our practices so that they can implement them.”

Graffeo has met with Hudson High School teachers and tried to do just that. She says the responses she has seen from teachers have been mixed.

“Some teachers are like ‘Yeah, I’m ready to do this.’ Some are just so stressed out themselves,” Graffeo says. “Some are ready to try some new things, and others are imbalanced and their plates are too full.”

Graffeo explains that the primary reservation that teachers have about introducing these practices is time. Teachers of subjects like English, science, and math are held to strict pacing calendars that are often tied to standardized tests like MCAS or the AP Exams. In these classes, curriculums are written so precisely that teachers fear they will fall behind if they cut out time for stress reduction.

Graffeo insists, however, that these practices take very little time, citing a meditation session that Jamie Gravelle ran in her class.

Graffeo says that the meditation, which utilizes a phone app called Mindful Shift, took less than five minutes to complete. She adds that meditative practices have a proven record of bettering academic performance among students.

“There are studies that show that kids need to turn off the screens and shut off everything that’s stressing them out in their world and just take that moment to focus and to re-center themselves,” she says. “[Once you do that] you’re going to be firing more neurons. It’s going to be awesome. You’re going to be so ready to tackle the world.”

Still students rarely see stress confronted outside of their wellness classes or, for a select few, their counseling sessions. Hudson Public Schools realize the problem that their students face but have been forced to battle incrementally for the changes they need to make.

“I think we’re moving in the right direction, but making cultural change is a slow process,” says Gravelle. “Policy change is a slow process.”

From Academic Stress to Hospitalization

As Hudson has worked to make the policy change needed to solve its mental health crisis, some of the most alarming statistics measured by the MetroWest Health Survey have remained unchanged.

In 2014, when the last MetroWest Health Survey was administered, 14% of Hudson High School students said that they had considered suicide while 4% said that they had actually attempted suicide.

“It, to me, mirrors what we’re seeing in a broader scale,” says Hudson High School Principal Brian Reagan. “From a school perspective, what we’re seeing is a mental health crisis that is not getting better. It’s getting worse.”

The measures taken by Hudson Public Schools have also failed to reverse an uptick in depression at Hudson High School. In fact, the survey showed a 6% increase in depression symptoms between 2010 and 2014, while the number of students reporting self-harm rose by just under 5%.

In 2014, close to one out of every four students in Hudson said they were depressed, while nearly one out of every seven students said they had considered suicide.

In the most severe of these cases, Hudson students have had to leave school for prolonged stretches of time. Though data on these absences is not readily available, the Big Red spoke to one student who did experience such an absence.

“My time away from school was caused by a lot of things,” the student, who will remain anonymous, said. “Some of it was mental health, a lot of it was school, and some of it was stress from home, but school did play a major role because on top of everything else, school was something that I didn’t really expect was going to be hard for me.”

This student missed a significant amount of school after a severe mental illness left her hospitalized. She explained that she had been surprised by the amount of stress that she encountered at the start of the school year.

“I had never thought I had a problem with school,” the student said. “When I finally had time to myself to think about what led up to my being out of school, I realized that it was a big part. I was putting way too much pressure on myself, and I was getting into a bad head space.”

For this student, a drive to get good grades rapidly morphed into a pattern of self-hate that continued to send her into a deeper depression.

“I started to get down on myself a lot just because I would be mean to myself over the stuff I wasn’t doing,” the student said. “When I got a paper back and it wasn’t the grade that I wanted, I would think, ‘Oh, I’m so stupid. I should have done better. I can’t believe I would do that. That’s not who I am.’ I would just treat myself really badly over it.”

The student’s eventual hospitalization was caused by many of the same stresses noted by classmates. She would get large amounts of homework and stay up until between two and three in the morning worrying about getting her homework done. The student’s stress about homework left her isolated from friends and family. Furthermore, good grades from as far back as sixth and seventh grade, when school was much less demanding, made the student feel like she was failing when she could not get As for her work.

When the student reentered school a few months later, she found herself at the beginning of a long process of getting back to her regular classes. The student says that she initially expected to be back in her classes within a few weeks of coming back to school. She actually spent months working with tutors to get up to date on the work she had missed.

In the wake of her absence, the student dropped one of her rigorous classes and says that she had her needs taken seriously by the teachers who helped with her return to school. The student says that she was happy that her teachers did not make a big deal out of her absence and noted how her Therapeutic Academic Support teachers helped substantially with pacing herself and keeping her from getting overwhelmed.

Throughout her battles with mental illness, the student says she has run into stigma that has at times prevented her from getting help.The student says that before her hospitalization, she pushed down symptoms of depression for fear of getting judged by classmates.

“Me, I’m a very social person. I do have a lot of friends, but I think that a lot of kids associate loners with people that struggle with depression. I kind of hid that from people because I didn’t want to be known that way,” the student said. “I didn’t want people to think of me differently. That was a really hard thing for me.”

Beyond keeping her from getting help, the student says that stigma also made it hard for her to drop one of her classes that was causing her stress.

“Looking at the workload I was thinking, ‘I can do it. I can get it done.I don’t have to drop this class,’” the student said. “I think the stigma about dropping a class was really getting to me, and I didn’t want to be that person who drops a class.”

The student is not alone.

Sophomore Elizabeth Cautela now sees a therapist to help with her stress about school. She says that even that fact alone has confused her classmates and revealed ignorance about mental health treatment in the Hudson High School student body.

“One time we were at lunch, I don’t know what we were talking about, but I mentioned my therapist, and someone said, ‘Why do you have a therapist?’ Like almost I’m crazy or something that I have a therapist,” she explained.

HHS has tried to battle stigma through the evolving wellness curriculum. Jamie Gravelle says that she believes that programs like Break Free From Depression have made progress in exposing students to mental health issues and breaking down myths about mental illness.

Data from written tests administered before and after the Break Free From Depression Unit confirm this. According to the tests, knowledge about mental illness increased from 27% to 82% over the course of the unit.

However, Gravelle admits that more work has to be done to completely erase stigma about mental illness. She adds that change needs to be made on a widespread level.

“It’s not, to me, a school response only,” she says. “It’s a community, public health issue.”

In High School, the Gold Trophy Is Certain

In an article published in March, third grade student Gavin Capobianco described his own stress to the Big Red. Capobianco attends elementary school in Hudson and faced considerable stress about MCAS this spring.

“It’s like if you’re trying to do your best in a race, and there’s a gold trophy,” he said of his stress. “You’re trying to get it, and then you don’t get it.”

In interviews conducted since then, Capobianco’s sentiment has rung true–even for college-ready teenagers who no longer have to take MCAS. The gold trophy still exists for Hudson’s oldest students, perhaps even more prominently than it did in elementary school.

For Gavin Capobianco, stress is tied to the fear of disappointing his teachers with poor MCAS scores. For high school students, stress is tied to the similar, but far more impactful, gold trophies that are SAT scores, GPA values, and college acceptance letters. Feeling that they must grasp these trophies, students often sacrifice their own mental health, in the form of sleep, connection, and down time, to finish a paper, or study for another hour ahead of a test.

The costs are substantial, but, in the minds of some, necessary.

“My exhaustion level has been so high consistently that I often think, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m a zombie of my freshman self,’” explained Scott Kall. “I remember the days where May was my favorite month of the year, and I’d always be out playing basketball in my driveway. I physically cannot do that anymore. Part of me is sadder just because I don’t have the time. But at the same time, it’s an important part of growing up. The sooner that you have some more pressures on you, the sooner you’re gonna get used to that.“

What starts as crying over homework after an hour of struggling at the dinner table in third grade, students say, can turn into more stress, and the kind of troubling mental illness that has sent some of Hudson’s students to the brink of suicide by high school.

“I feel like I have to keep running and working and doing the best,” says Elizabeth Cautela. “That’s going to be my downfall. I know that that’s already my downfall. But it’s not stopping me from being the best that I can be.”

Cautela says she finds particular poignancy in the idea of a gold trophy being central in her education. She has followed a path that is in some ways similar to Capobianco’s. She has long stressed about school. It has caused her to suffer from panic attacks and bouts of insomnia and restless sleep. But just as Capobianco focuses on getting the right answer on the MCAS, Cautela pushes through her stress with minimal help, watching her grade, picking apart her GPA, and scrutinizing her junior and senior years ahead of her as she awaits the college acceptance letter that she has long sought.

“It feel like I have to be the best because we live in a world where, in order to be good at something, you need to win a trophy or be the best at something,” Cautela says. “They always say that no one remembers who comes in second; they only remember who comes in first.”

Siobhan Richards contributed additional reporting, photography, and multimedia design to this report.