by Dakota Antelman

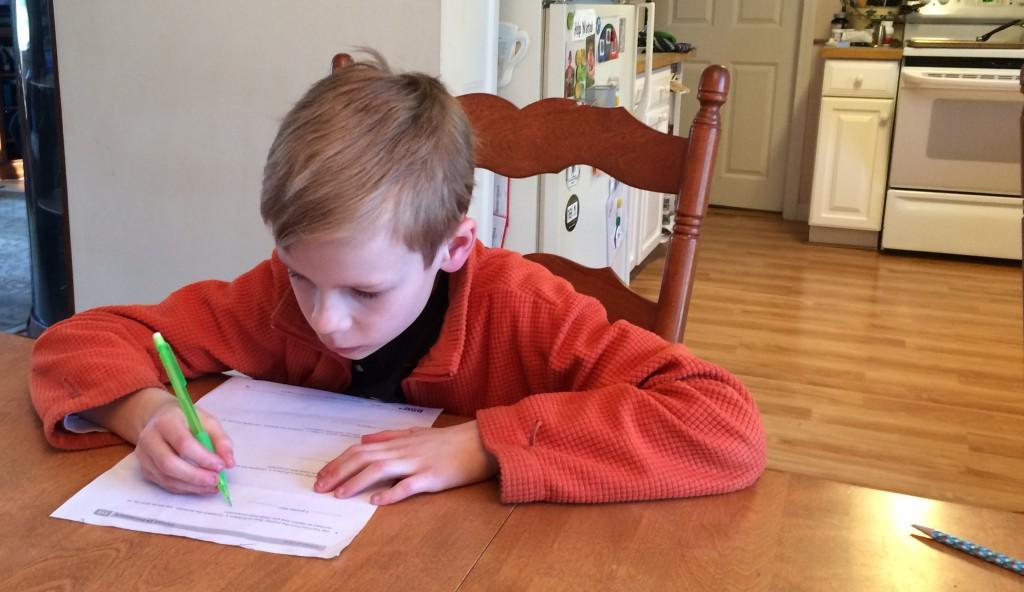

Third grader Gavin Capobianco sits at his dining room table, seated on his hands, with his feet dangling off the end of his chair. He has black marker smeared over his hands and face. A PBS kids show blares in the living room just over his shoulder — but he is no longer watching.

I ask if he is stressed.

He answers, “Yeah, sometimes.”

Capobianco struggles with a speech impediment combined with ADHD and a language processing disorder. He struggled to articulate the stress he felt in school, especially as he approached the third grade MCAS, which he took earlier this month.

According to his mother, Dawn Capobianco, a first-grade teacher herself, Gavin’s stress about taking the first standardized test of his life started months ago.

“He came home [in January] saying that the had a big test coming up,” she said. “He said this is what they had to learn, and this is what they have to do, and this is what they have to practice. He’s become anxious a lot earlier than I think is necessary.”

Since they started their school careers, Gavin Capobianco, his older brother Jaxon, and their mom Dawn, have together witnessed a change in the priorities of grade school education that has heightened stress and created long-term anxiety in children as young as six years old.

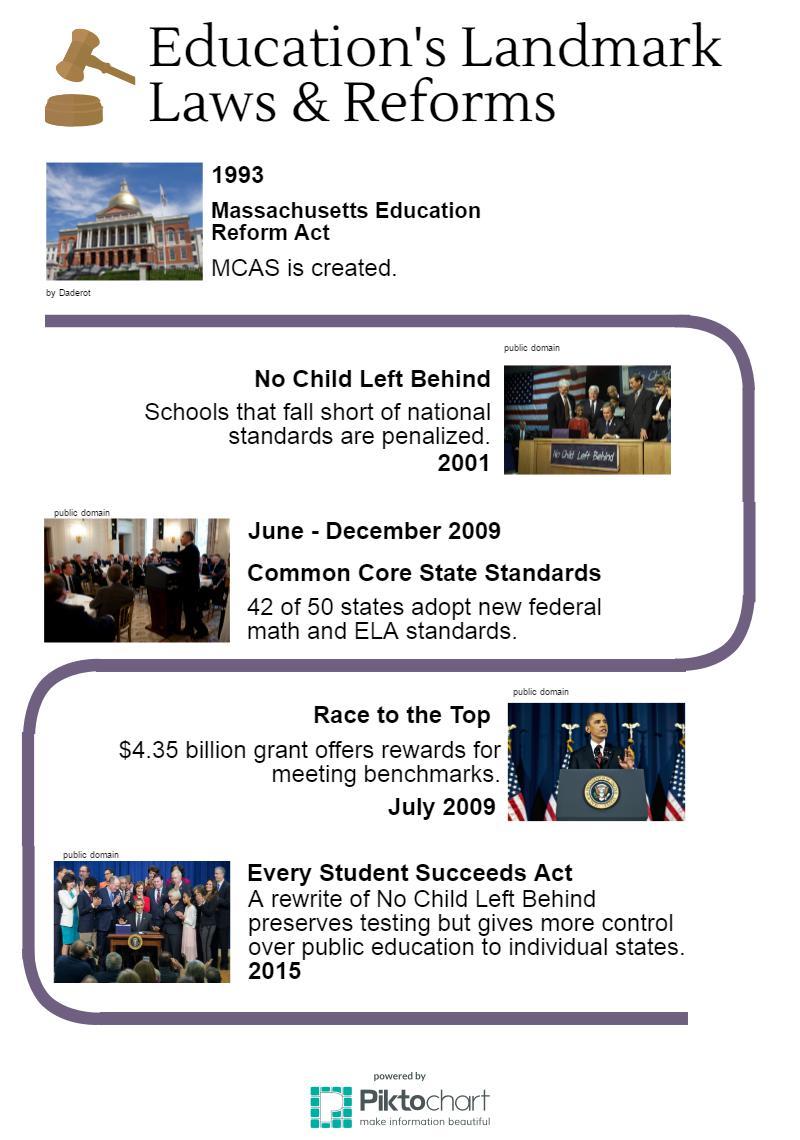

Experts within the education world acknowledge the increase in demands of students in school systems across the country. In 2001, the No Child Left Behind Act pressured states to raise the standards to which they held their schools. No Child Left Behind quickly propelled the schools towards a data-driven style of education. Testing inside classrooms increased, and one by one states began administering nearly annual standardized tests to students young and old. The Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) which had been in effect since 1993 was expanded to fit the standards of No Child Left Behind. Common Core was adopted in 42 of 50 states, adding additional benchmarks for schools to live up to.

Full Day Kindergarten

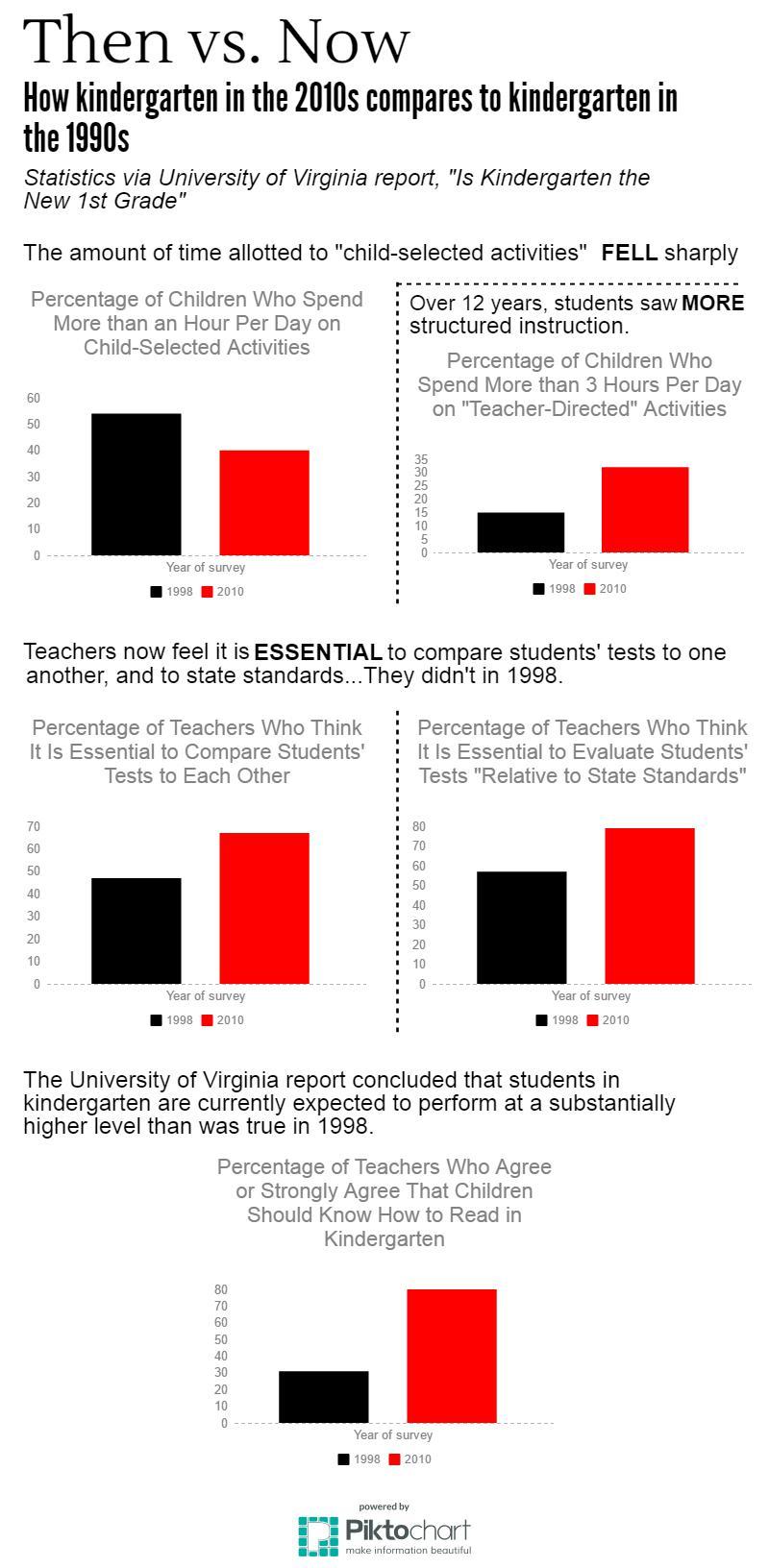

The rise in demands was not instantaneous, but it was rapid, and, according to some, it is not yet over. The idea that “Kindergarten is the new first grade” has gained particular traction as educators once trained to teach “play-based learning” in their classrooms have reacted to new curriculums, more structure, and less freedom for children.

“The curriculum demands have really increased a lot in the last seven years,” Kim Colbert, a Hudson kindergarten teacher who started teaching seven years ago, said. “I do maybe a couple things I did during the first year. Otherwise, I would have to say that 95% of the things I did that year I no longer do.”

Colbert says her day has become more and more structured around math and literacy, two subjects placed at the forefront of the No Child Left Behind initiative.

She teaches one hour of math each day, broken up between a group lesson and specific “centers” where students practice math skills taught that day. In addition to math, reading and writing are allocated daily blocks of time. She tries to fit play into those lessons, while also educating students on social studies and sciences.

As she wrestles with her daily schedule, trying to fit in reading, writing, and math lessons, Colbert finds it increasingly difficult to find time for skills she thinks are the most important for kindergarten students to learn — social skills.

“I think the social piece sometimes gets lost with the reading and the writing and the math,” she explains. “It’s something that we have to consciously focus on to make sure that the kids get it because the day goes by fast.”

Colbert emphasizes that learning how to interact with other kids is something that students must be taught. She believes teaching kids skills such as turn taking and asking for things is crucial in setting the groundwork for later education. She worries about making sure that remains a part of her school day.

Her fears are shared by Hudson Public Schools Superintendent Jodi Fortuna.

“What we see is a lack of resiliency,” Fortuna says of the consequences of failing to provide proper social skills education to students. “When something goes wrong, they lose the ability, sometimes, to bounce back from it.”

Half Day Kindergarten

A colleague of Colbert’s, Kathleen Nugent, is faced with a different, and perhaps tougher task of adapting to the new standards. Nugent, who has taught preschool and kindergarten classes for over 20 years, currently teaches half day kindergarten.

Nugent’s classroom is speckled with crayon drawings and colorful posters on its walls. It does not betray the stark changes Nugent herself has had to deal with in the seven years since she moved from preschool education to kindergarten. Her struggle has been amplified by the fact that she has half as much time as Colbert to teach the exact same curriculum.

“[In the past] I had more flexibility as to when I could pull things in and when not to,” Nugent said. “Now we’re really on a pacing calendar, so you have to keep pace. We also have to align with the full day, so that kind of keeps you to a schedule that limits your opportunities for flexibility.”

Nugent tries to weave play into her lessons, but her ability to do that is limited by the curriculum and the pacing calendar she must follow.

“I try to make it fun. We play games. Sometimes when I’m teaching them a sight word, we do a recipe, and I make it with them,” she says. “I try to give them some play in different areas, but it’s not child-directed play.”

Another damper on the free play of kindergarten is testing, an aspect of kindergarten for which Nugent spares no love.

“There’s way too many, way too many,” Nugent mutters of the number of tests she administers to students. “Somebody counted last time..[and] it came out to some ridiculous number like 13 assessments for the first half of the year. It was too much.”

The tests that Nugent and her colleagues administer are pushed by the curriculums chosen by the Hudson Public School district. She explains that not all the tests are mandatory in an individual sense, but says, “You have to have data to prove that the kids are improving.” Nugent and her colleagues are troubled by the testing and have worked to weed out unnecessary tests.

Nevertheless, they continue to hand out tests at the end of each module of math and in correspondence with their regular lessons in literacy.

Beyond the testing, Nugent and Colbert have been introduced to a parade of new curriculums and demands through their years as teachers. Colbert notes that the reading level students must be at by the end of kindergarten has been increased twice in the past seven years.

Nugent explains, “In order to address the Common Core and in order to align the schools, they (the Hudson Public Schools) have explored new programs. Over the last five or six years, there have pretty much been new programs and new curriculum framework guides on a regular basis.”

Reader’s Workshop was the first program to be added after Nugent started teaching kindergarten. Soon, Hudson Public Schools adopted Fundations, a new curriculum for phonics. Shortly after that, the district amended the daily Writer’s Workshop. Then, at the beginning of last year, as part of a district-wide overhaul of math education, a group of Hudson teachers and administrators elected to transition Hudson Schools to the Engage New York curriculum.

Nugent has mixed feelings about the regular curriculum changes.

“You’re learning with the kids [when you teach a new curriculum], which is stressful for the teachers. But it’s good because you’re getting feedback from the students in what they’re more comfortable with and where you need to adjust things,” she says. “I do like the high standards, but I don’t feel like all aspects of all of the programs are best suited for all the kids all the time.”

Overall, Nugent, Colbert, and many kindergarten teachers in Hudson and across the United States together wade through what Nugent describes as “a hard time for teachers, and a hard time for students.”

Demands are increasing as five and six year olds are being expected to read at a higher level and understand more complex math than they were a decade ago.

Reflecting on the change, Colbert says, “I think what is important to remember is that they are five and six years old and that they still need to be able to be five and six years old. They still need to be able to be kids, and I want to make sure that that continues.”

Elementary School

The demands of No Child Left Behind, Common Core, and other initiatives like Race to the Top, which was an optional program started in 2009 where schools could gain extra funding for meeting certain benchmarks, all converge in elementary school, where standardized testing and, in many cases, noticeable academic stress, start.

Like kindergarten, literacy and math remain at the forefront of early elementary education in particular. For much of first and second grade, these skills remain central in classrooms as teachers eye the first MCAS students must take in third grade.

The preparatory qualities that these classrooms sometimes take on has made it so that elementary school has evolved in many of the same ways that kindergarten has.

“I think the rigor has really ramped up in all levels but especially in the elementary,” first grade teacher Karen Eadie says. “There’s a lot more expectations, especially in early childhood education. I also used to see a lot of play-based learning.”

Eadie notes a rise in assessments, similar to that observed at the kindergarten level. She says that first grade students currently end each year having taken 48 formal assessments during the 180-day course of the school year. When distributed evenly over that 180-day span, students average taking one test every 3.75 days.

“The purpose of assessing is to see what a student is struggling with and what they don’t know yet,” Eadie says. “But we’re spending way too much time assessing when we could be instructing or even just sitting next to a student and helping them with something in a less formal, rigid way than a formal assessment.”

As is true in kindergarten, Eadie says these tests stem mostly from the curriculums selected by the Hudson Public Schools. She says she works hard to make sure students do not feel unnecessary pressure on the tests, calling the assessments “show what you know(s)” when speaking with her students.

Nevertheless, she says, especially as students get older, the rigor of the lessons taught to them can apply stress.

“I know that 3rd and 4th graders do feel a lot of pressure to do their best,” she says. “It’s sort of a fine line to walk. You want them to know this is important and do their best. But also, it’s not the end of the world if you don’t do well.”

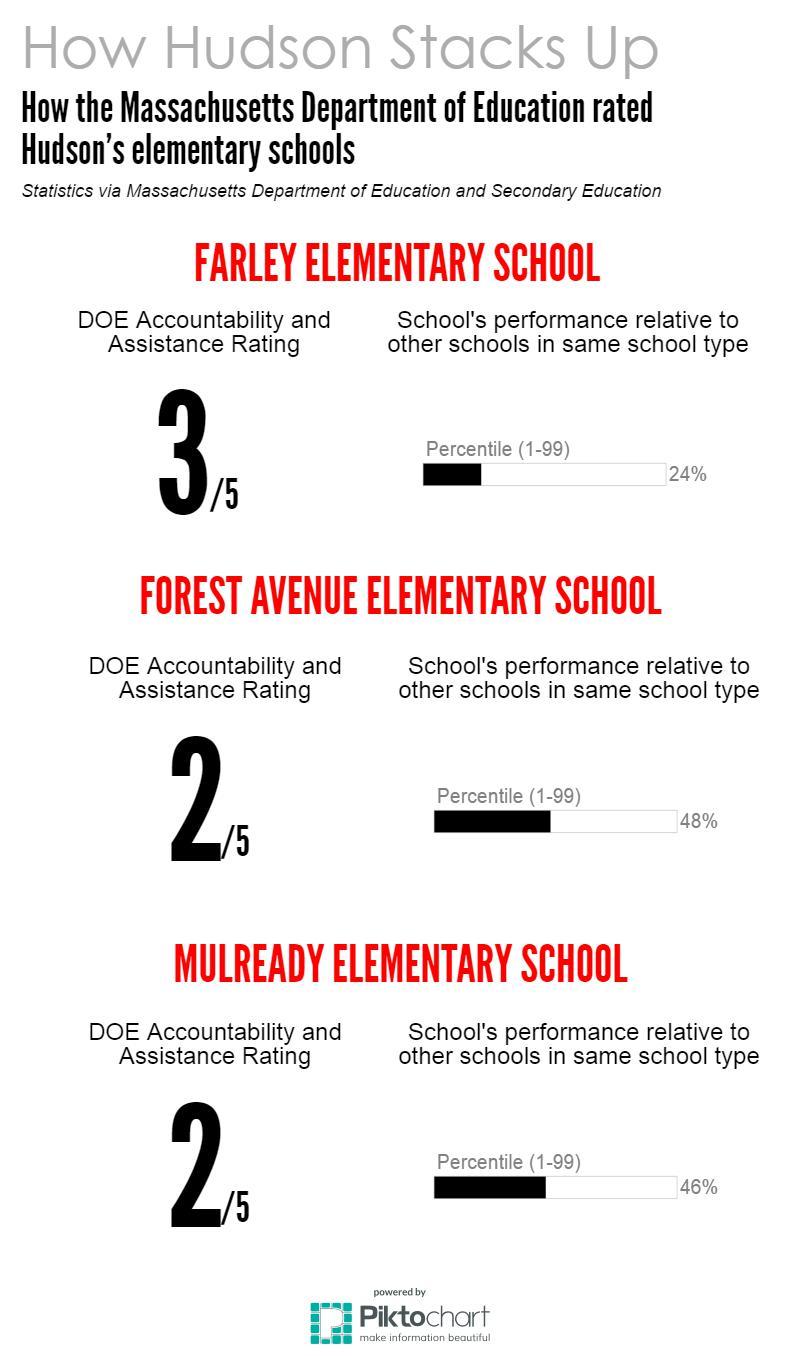

Eadie’s is a conflict faced by many in elementary education, especially with regards to MCAS. Though individual students do not suffer consequences for poor performance on MCAS tests until 9th grade, MCAS scores carry massive weight for administrators in the middle school and elementary levels. MCAS scores for demographics within schools are key in the Massachusetts Department of Education’s (DOE) rating of every school in the state. Every year, data from every school statewide is analyzed by the DOE, which in turn assigns a rating, on a scale of 1-5 (with 1 being the best rating) to schools and school districts.

Poor ratings can have grave consequences for a district, ranging from minor interventions from the state, to total take-over of a district by the DOE. For Hudson, which was recently rated a level three school district in 2015, raising MCAS scores has been a topic of stress for administrators.

“I don’t ever want kids to feel pressure but without a doubt, administrators, teachers, we do feel pressure because we have to,” Forest Avenue Principal David Champigny says. “You don’t have a choice.”

To keep the pressure off elementary students, Champigny and the Forest Avenue staff configure testing so as to preserve recess and “specials” like gym class for students during testing days. Teachers also work to convey a “do your best” mentality to parents and students.

“Our teachers do a good job making kids understand that they’re not a number,” Fortuna explains. “But kids are like sponges. They pick up on the environment around them. I think they feel the inherent stress that school districts feel, and individual teachers feel about the accountability. I don’t know how to combat that.”

Third grader Gavin Capobianco, has, as said earlier, suffered from anxiety for over two months as he prepares to take his first MCAS test.

“It’s been a lot of anxiety for him,” his mother Dawn Capobianco says. “It’s coming from the school. It’s not coming from home. It’s not something that my husband and I emphasize at all at home.”

Dawn Capobianco reached out to the teacher who first introduced the MCAS to Gavin through e-mail, detailing her concerns about her son’s anxiety.

“She explained that she had presented it more as a game and a challenge; that it was something that they were just gonna do so that teachers could find out what they know,” Dawn says. “But it obviously placed a lot more anxiety in Gavin.”

With the MCAS much nearer now, Gavin remains worried about the test.

“The teacher did say a few days ago that everyone would do fine, but I’m not sure if she’s right or not,” he says, trailing off.

The school does not want to cause students undue stress about MCAS. Needless to say, grade school students do enter testing rooms each spring worried about how they will score.

One source I spoke to for this article has a middle school student in the Hudson Public Schools and until recently, had a son in one of Hudson’s elementary schools. She requested anonymity to protect her children’s identities.

Though neither of her children say they suffer stress relating to MCAS, the source suggests that the reason some grade school students do is because of an overcompensation by administrators and teachers in their goal of making the MCAS seem like nothing more than a test on which students should do their best.

“I went back to the elementary school. My kids aren’t there anymore, but I went back for music lessons with one of them, and the stuff I saw on the wall was all about MCAS,” she says. “It was for a pep-rally for MCAS, but a lot of parents told me that that was actually very stressful to their kids. That made it into such a big deal by trying to make it fun. It still was all they talked about.”

Schools in Hudson are working hard to improve on MCAS scores that have fluctuated in recent years. On a district level, teachers and administrators have tried to remedy issues with literacy and math by introducing new curriculums across the district. In the elementary level, like the kindergarten level, these curriculum changes have, at times, disrupted classrooms, and left children who struggle to understand them behind.

For the source mentioned earlier, she saw her son struggling with the Engage New York math curriculum.

“When they changed the curriculum, they specifically told me that my son shouldn’t have a visual math curriculum,” she said. “It was just the wrong curriculum for him. I liked the curriculum, but it didn’t fit his needs. When he would say he didn’t understand something, they kept trying to re-teach him from the same curriculum. That really stressed him out. He was not having another way to learn the work. There was not another way to get accommodations. That’s what was frustrating.”

The source’s son was frustrated and angry about what was happening in school. She says by the end of last year, he was “close to a point where he didn’t like school anymore.” Beyond that, she said he seemed scared.

“I think he sees the writing on the wall and gets nervous about throwing in the towel now,” she says. “He will beg for help, but they don’t know how to give it to him.”

The source acknowledges that the curriculum is not as rough for students this year, but attests to the fact that curriculums will always be better in the second year that they are taught. For her son, regular curriculum changes in reaction to data collected routinely caught his grade in that stumbling first year of implementation.

His grade, over the course of several years, was taught the first year of a new spelling curriculum, a new writing curriculum, and finally last year’s new math curriculum.

“There’s always a shift when teachers learn a new curriculum. The first year never goes well,” she says. “But if you have a kid that’s in that first year of the new curriculum, that’s not comforting to you.”

This source understands the motivations behind these curriculum changes, but she finds herself caught between competing emotions.

“I look at the metadata, but then I look at my individual kid,” she says. “Sometimes these decisions make sense on the big scale, but they don’t work for my kid.”

Superintendent Fortuna, who, before taking over as superintendent, spent time as the principal of Forest Avenue, defends the changes, saying that they were made to “catch up” to state standards.

“We never had a written curriculum in Hudson. I could walk into one second grade class and see one lesson, and then see something totally different in another second grade class,” Fortuna explains. “It wasn’t so much different teaching styles, because teachers should have different teaching styles, it was totally different content. One day, I remember I was doing a walkthrough, and I saw the same exact lesson in grade two, grade three, and in grade four. It was a math lesson. And that really brought home the need to have this written curriculum that progressed along with the students.”

The curriculums themselves bring about new homework that can create stress for students in the home. In kindergarten, this homework is minimal, and, according to Kim Colbert and Kathleen Nugent, it is intended to be a fun way for parents and students to communicate about what they are learning in school. But once students move through elementary school, the demands of homework assignments intensify.

In third grade, students like Gavin Capobianco are expected to review their math facts, read for at least 20 minutes each day, and normally complete a double-sided hand-out each night. The handbook drafted for all three Hudson elementary schools says homework should take no longer than 40-45 minutes per night.

For Dawn Capobianco and her youngest son, however, homework often takes longer than that.

“I would say we call it quits a lot of nights after the 45 minutes to an hour no matter what he’s done or how much he hasn’t done,” Dawn says. “For him it would take a good hour and a half, and that’s if he remained focused.”

In an interview conducted in early March, Gavin Capobianco discusses his experience with homework.

Gavin does suffer from a learning disability that makes staying focused in school and while doing homework difficult for him. He is allowed accommodations in school and on the MCAS thanks to an IEP his parents had to battle with the school district to gain.

Dawn still looks at the homework load, however, and says, “This day and age, with so many kids participating in after-school activities, it’s really hard to get all of those things in and have a family dinner and still get kids to bed on time.”

For young children, not having enough sleep can amplify stress problems in school and at home.

Homework in general is a topic of disagreement and debate among parents, teachers, and administrators. The same unnamed source mentioned earlier says she feels that some homework in early elementary is unnecessary.

“When you ask why are kids getting this homework in second grade, the answer is that it’s to prepare them for third grade. Why do they get that homework in 3rd grade? They need to prepare for the homework load in fourth grade,” she says. “It’s almost like we give kids homework, so they can learn how to do homework, which teaches them how to do homework.”

High stakes testing and regular formal assessment can breed inadvertent test anxiety. Misunderstanding a curriculum and then being saddled with time-consuming homework after a long day at school creates further stress for young students. More so, it causes some of their parents to fear how that anxiety will grow as academic demands increase.

“I have a kid, he is in fifth grade, and he is already stressing out. He’s already worrying about not getting into Duke for college,” the unnamed source says. “I look at that and think about how we put so much pressure on them from a young age. Now, it’s gotten to a point where it trickles down, and he’s in fifth grade worrying about what college he will get into.”

Middle School

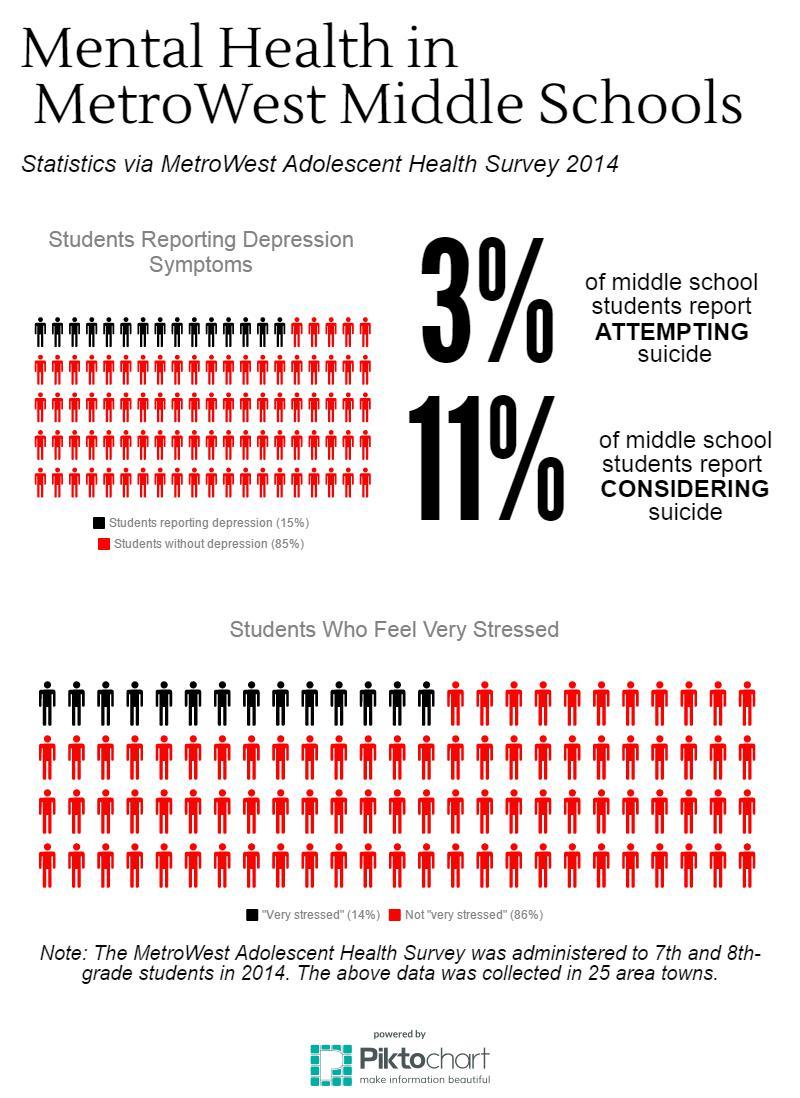

Students who deal with stress in high school often point to their middle school years as the point at which that stress was born. There, grades become emphasized in a way that they never were in elementary school, with homework and test grades being input into iPass. Furthermore, MCAS and the demands of Common Core continue, but with a new eye towards high school and post-secondary school preparation.

“Middle school is the transition between elementary school and high school, so more pressures are being applied onto kids at this level,” explains Quinn Middle School principal Jason Webster. “How they respond to having more responsibilities is where the stress comes from.”

Webster notes the increase in extracurricular activities offered to middle school students. In addition to that, he acknowledges a spike in homework noted by multiple middle school students.

Chris McDonald, a sixth grade student at Quinn, said his homework load doubled between fourth and fifth grade. He says he knew that the demands would increase but admits that “sometimes, it’s a little too much to handle.”

McDonald spends roughly two hours on homework each night, falling within a spectrum of time spent on homework that Webster estimates could be wide ranging.

Though there is no formal policy in place, Quinn informs its parents at the beginning of each year that students can expect between one and two hours of homework.

“But that is just a guestimate,” Webster stresses. “We have a lot of kids who work really hard, and it takes them 2.5, 3.5 hours, maybe more to get things done. We have other kids that go home and had it done during school, so they don’t have as much time perhaps spent on homework.”

Parents confirm that homework is a stressor in their children’s life. Dawn Capobianco, whose older son Jaxon is currently enrolled in sixth grade, says it is even a struggle to have dinner as a family given the stress caused by her son’s homework.

In addition to dealing with normal academic stress, Jaxon has to deal with the added pressure caused by a learning disability. Because of these challenges, Dawn feels she needs to be in regular communication with teachers.

“The middle school teachers are great, but they definitely have the mindset that our children are getting older and need to be independent and need to follow through with things on their own,” she says. “They encourage the students to be the ones to contact them with questions and things. That’s been a little trickier as I’ve had concerns. I want the teachers to know that he still has parents that need to oversee what’s going on. At 12 years old, he can’t be responsible for all those decisions.”

Webster in turn stresses that independence, strong work ethic, and self-advocacy are all traits students must develop prior to moving up to high school.

This new responsibility, with regards to both independence and workload, is not lost on incoming students, who enter middle school knowing the work will be harder, but not knowing how hard “harder” will be.

The daughter of the unnamed source mentioned earlier is currently in sixth grade. She says she enjoys middle school more than elementary school. Nevertheless, she and her mother attest to the fact that she felt massive amounts of stress in the summer before last year.

“From probably about February to July [she] would burst out crying about the transition that she was going to be leaving her old school and going to the new school,” the source says. “I talked to other parents, and that was not unusual.”

The source explains that there was close to no introduction to middle school for her daughter in fourth grade. She explains that her daughter feared the unknowns, adding that simple familiarization with the schedule and the setup of the day could have helped to ease the stress her daughter felt. This source notes that in past years, there had been a district-wide “Fly-Up-Day” where students would spend one day in the next grade level to better understand what their school day would be like the next year. She explains that that program was ended due to complications with busing and accounting for such high numbers of students.

In the two years since that transition, Fortuna has worked with principals across the district to ease the transition. Last year, the Fly-Up-Day was revived. Fortuna was unsatisfied with the results however. In the time since then, she has worked with elementary principals and Quinn Middle School principal Jason Webster to build multiple opportunities for students and parents to become acclimated to the middle school. Students and parents will be able to attend a nighttime event where they are given a tour of the school and familiarized with the daily routine of middle school. Fortuna also says she hopes to integrate families into the school by getting them subscribed to the weekly email newsletter sent home by Principal Webster.

In Pursuit of a Gold Trophy

Gavin Capobianco describes the general stress he feels relating to school.

Students in grade school do not have transcripts or permanent records. Many still long for play and hands-on learning. Some cannot speak fluently. However, they are increasingly being handed work that would, before reforms like No Child Left Behind, have been seen as too advanced for their age group.

Reflecting on the increased rigor of school in general, David Champigny of Forest Avenue Elementary School nods his head as he says, “Yes, it is harder to be a student now than it was 10 years ago.”

Students feel pressure to perform in the classroom, and they feel indirect pressure to score well on high stakes tests like MCAS. They sit in class and try to absorb concepts taught by teachers who must follow new and unfamiliar curriculums. In turn, these curriculums must abide by federal and state standards set in the wake of No Child Left Behind 15 years ago.

As they do so, teachers are left asking questions like the one Kathleen Nugent asks. “They can add two plus three, but they can also add 17 plus 15. How far do we go?”

Those involved with the district look at such questions and say that the Hudson Public School system, like many school systems across the state and the country, is in a state of transition.

Parents like Dawn Capobianco and the unnamed source find little comfort in that. They instead see their children struggling at times. They look at education in the ways that it has changed and question the merits of such changes. They see moves further down the path of data-driven education and feel frustrated.

“To me it’s a disservice to a human person to look at a number and make a judgement on them based on a number on one test,” first grade teacher Karen Eadie says. “There is so much more to one kid than a number. The people who are interpreting don’t know anything about that child. They don’t know what their strengths or weaknesses are, or what was happening the day of the test.”

On the receiving end of this are students themselves — students like Gavin Capobianco, who in third grade, feel stress over their test scores.

I ask Gavin what will happen if he does not do well on the MCAS.

“The teacher did say that I might not get a good score,” he says.

I ask why he feels he needs to get a good score.

He responds, fighting through a speech impediment, searching for his words as he articulates sentences to me, “To me it’s like if you’re trying to do your best in a race, and there’s a gold trophy. You’re trying to get it, and then you don’t get it. It’s just like that.”

For Gavin and many of his classmates, school is a stressful pursuit of a gold trophy that, though they do not know why, students feel they have to grab.

Ultimately, Karen Eadie concludes, “We’re working so much harder, but we’re not much smarter.”

Your Favorite • Jun 1, 2016 at 1:43 pm

good work bro. keep it up man, love ya.

Ms. Wallingford • Apr 7, 2016 at 6:59 pm

Dakota,

I’m impressed by your clear and fluid style, and by your thorough investigation. It’s a well-written piece that you should be proud of.

As a parent and educator, I believe that my children and students should struggle from time to time; struggle or difficulty is a natural part of learning new skills and content. And of course, it’s tricky to walk the line between work that is challenging and work that is overwhelming, or between setbacks that develop resiliency and setbacks that create defeatism. That’s just one of the reasons why parents and teachers have such difficult, and important, jobs.

Excellent work on this article!

Ms. Wallingford

Megan M McAuliffe • Mar 31, 2016 at 10:23 pm

Thank you for a very informative and well written article that opens up the conversation on many different levels. As a parent of a special education student who only received an appropriate learning environment for her child once she hired an attorney, I find the following sentence to be quite telling of the HPS environment: “He is allowed accommodations in school and on the MCAS thanks to an IEP his parents had to battle with the school district to gain.” It’s unfortunate that parents feel that receiving appropriate assistance for their special education student is a battle. Why must parents battle for their special needs children?

Another quote hitting close to home is the following, which led to increased anxiety, lower self-esteem and distrust: “I think he sees the writing on the wall and gets nervous about throwing in the towel now,” she says. “He will beg for help, but they don’t know how to give it to him.” Why don’t they know how to give the help needed?

~Megan McAuliffe

Filipa Filipe • Mar 31, 2016 at 12:29 pm

Impressive reasoning and writing style of such an important matter. I had to share it with all my “international” contacts. Well done, Dakota.

Kim Colbert • Mar 31, 2016 at 12:57 am

Well done Dakota!

Joshua Otlin • Mar 30, 2016 at 11:53 pm

Outstanding work, Dakota. This is an intellectually honest examination of tremendously complicated, important issues. The manner in which you blend individual narratives and voices within a story about broader national, state, and local policy changes is excellent.

In your future work, I hope you might help your readers understand more about how things came to be this way. Early in your piece you provide a brief review of Education Reform in Massachusetts, NCLB, RTTT, and ESSA; a more thorough examination of these laws may help your readers gain important insight into the current state of affairs. Each of these laws resulted from extended battles between individuals and organized groups with competing philosophies and interests, and each battle had clear winners and losers. Understanding who won, why they won, and how they won is important for anyone who cares about American public education.