Jackson O’Brien, Neil Rao and Chase Boluc on a recent mask break. Rao is one of approximately 14 students who identify as AAPI | photo by Avani Kashalikar

Speaking Out: Asian-American and Pacific Islander Students Share Their Experiences on the Rise in Hate Crimes

Asian-American and Pacific Islander Students Share Their Experiences on the Rise in Hate Crimes

On March 16, Robert Aaron Long shot and killed eight people at three different spas in Atlanta, Ga. Six of those people were Asian-American women. He was charged with eight counts of murder and one of aggravated assault.

Freshman Savannah Gao said she learned about the Atlanta incident from her mom. “I wasn’t even shocked at this because it happens so often.”

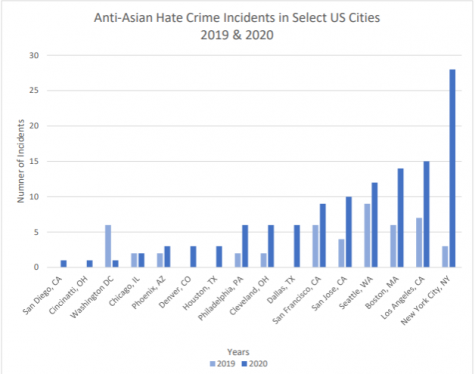

Hate crimes targeting Asian-Americans rose by nearly 150 percent from 2019-2020, according to NBC news. This fueled the Senate to pass bipartisan legislation to increase law enforcement to better protect the Asian-American and Pacific Islander, (AAPI) community. The legislation will now go to the House of Representatives.

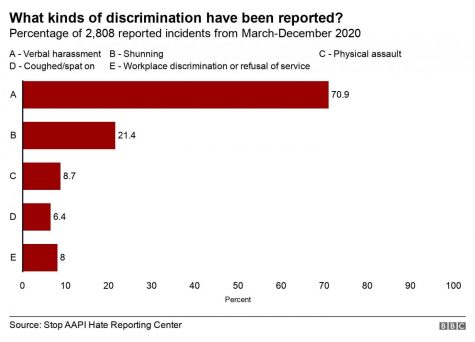

Around 3,795 AAPI hate incidents were reported to the Stop AAPI Hate organization between March 2020 and Feb 2021, however, there are many more that go unreported.

“It was kind of everywhere,” a student who requested to remain anonymous said.

Situations like these bring up the aspect of safety.

“I’ve been more conscious in public… just being more aware of my surroundings, just in case something does happen,” freshman Thuy-Tien Nguyen said.

“If I go to another town or city I don’t feel safe,” Gao said, mentioning that Hudson felt safe because she knows the residents.

Former President Donald Trump was said to play a role in the sudden spike of Asian hate crimes. He has called Covid-19 the “China Virus”, which has pushed many to associate the deadly virus with East Asians.

“It’s not something you should choose to ignore,” said freshman Neil Rao.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Asian is defined as a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam. Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander is classified as a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

However, racial and ethnic identity is subjective and personal. A person who identifies as Asian or Pacific Islander may not fall under any or all of the above categories.

According to the Massachusetts DESE’s 2020 School and District Report Cards, student enrollment data shows that 1.5% of the Hudson High school student body, or roughly 14 students, identify as Asian-American and Pacific Islander.

Those students related their experiences and thoughts about these issues.

In general, many agreed that hate crimes and aggression towards AAPI students are not widely talked about. Senior Heeya Patel said that she has only talked about situations like these “that one time in my linguistics class.”

“Hudson just doesn’t really talk about it, to begin with,” Nguyen expressed.

“In our community, no one talks about racism,” Gao echoed.

“Even when they talk about it, they’ll say something, they may post something on Instagram or Snapchat or something like that, but they don’t do anything after,” Nguyen said. “They’ll say something if it’s trending.”

Many reflected on their non-AAPI friends’ reactions to these events.

“They are trying,” said H. Patel.

“My friends and I have talked about it,” Rao said.

However, some did not agree. Gao said, “I wouldn’t bring it up around them because I feel like they wouldn’t care.”

Overall, all interviewees agreed that not enough was being done. “If there was enough being done, the hate and crimes would be lower,” Gao said.

Hate is not an uncommon occurrence. “It’s been normalized so much we don’t even think twice about it,” said Nguyen.

“It is not weird to go up and say you smell weird,” H. Patel said. She then expressed how uncomfortable and weird moments like that felt.

The anonymous student described the experience, regarding the “eye thing” in which a person pulls on their eye to make them replicate what they believe East Asians to look like, something that many expressed to have been common in elementary school.

“I couldn’t tell… if that looked like me.” the anonymous student said. “It was an epiphany; I guess I do look different.”

“I even have a nickname because I don’t want people pronouncing my real name incorrectly,” Nguyen said.

Gao narrated a moment that has stuck with her since its occurrence. “I was playing basketball by myself when someone came up to me and was like ‘ching chong ching change… that encounter made me feel unsafe and self-conscious about the way I look.”

These moments have also translated to something that is vital to culture: food.

H. Patel explained how when she was younger, many would make comments about her food. However, when she brought in samosas, everyone thought it was so cool. “Apparently that’s a trend now,” she said.

Gao said she could recall moments when people would try her food and then “claim that it was disgusting.” She said, “I wouldn’t even wanna have my friends over at my house to eat my parents’ food because I’m scared that they are going to judge it.”

“They’d say my food was weird because it was different,” Nguyen said.

Food also ties into the culture, something that many AAPI students are accustomed to suppressing. “I don’t share much,” H. Patel said.

“I just can’t express myself freely,” said Gao.

“At the beginning, it was kind of hard, especially in elementary school, when people were just being introduced to people other than their own family,” Nguyen said in regards to embracing her culture.

“I get uncomfortable when someone brings up the word ‘china’ because I feel like they’ll say something wrong,” said Gao.

Regardless of the similar experiences that AAPI students share, they are not the same person.

“Some people think that Neil and I look alike, I don’t see it,” said freshman Mahir Patel.

The anonymous student mentioned the grouping that occurs for many Asians. A place with many different ethnicities and nationalities is classified into one group by peers. “‘Go back to China’ but they’re Korean.”

“Do you just see us all as the same person? Do you think we are all the same person and mush us together?” Nguyen said while discussing how the teacher would mix up her and another Asian-American student.

H. Patel expressed how there were many times when people would assume that she was related to another student of Indian descent, however, if it wasn’t true, they would immediately assume that they were in love. “You’re either brother or sister, or you’re in love with each other.”

Many echoed this sentiment, especially regarding being paired up with other students of similar descent. Even if it wasn’t mentioned, it was quite obvious that the reason the students were paired was not that they would be “cute” together, but because they looked similar.

“Do I fit into the Asian stereotype?” said the anonymous student. Stereotypes are a common yet individual experience for AAPI students. The anonymous student said that they do not like the stereotypes, “the problem is I fulfill them.”

Asian stereotypes span from the meek innocent girl to the successful student. The latter stereotype perpetuates the idea of being a passive model minority, which not only downplays the success many gain but also creates a racial divide by diminishing the systematic racial struggles of others. “Asians are seen as a model minority,” said the anonymous student.

“They assume that all Asians are super smart and have these really strict parents, which might happen but it’s not always true,” said Nguyen.

“They’ll say like ‘tech support’… it kinda does bother me… when they say it often,” said M. Patel.

“They expect all of us to be smart, but we are just like everyone else,” Gao said.

She then mentioned that those who are smart “are not naturally smart, we just work hard.”

“If I got something wrong, my friends would be like ‘Oh my god I’m as smart as Ti-Ti’… I’m not a human calculator,” Nguyen said. “If I get an A+, and a white student gets an A+, and sometimes they will give the white student more gratitude because they kind of expect me to get the A+ anyway”.

Similarly, the talk of the future is something that Nguyen has had many uncomfortable situations with. “Oh colleges will love you, ‘cause you are Asian, you are a minority, and sometimes it’s the opposite like ‘oh you’re Asian you can’t get into this school because they already have too many Asians’…I don’t just go around pinpointing what everyone’s goals are going to be, like they expect you to have good grades all the time, or always know the answer.”

“The way people think of us is different from how we really are,” she said.

“People should recognize these gestures that affect us,” Gao said. “I don’t feel like it’s my job… It should be common sense… We live in America, there is so much diversity, you can’t be self-centered about your race.”

“Google’s free,” H. Patel said. She agreed that it is not her job to answer questions about Asian hate.

“I hate how some white people think it’s okay to speak for us. ‘Oh well this person doesn’t experience it because I’ve never done it to someone so no one else does it’ This is a whole population we are talking about, not just you,” Nguyen said. “Just because you don’t do it, like maybe you’ve liked something that might be racist, or your friend is racist and you don’t stop them; you don’t say anything. You’re still contributing, you’re still letting the problem happen.”

“I’ve become more passionate about it; I don’t care about how uncomfortable it is to talk to other people about it.”